Fish – a prized commodity

Fish – a foodstuff and the stuff of legends

For millennia fish have been a vital source of human nutrition. Archaeological finds suggest that people have been catching fish since the Stone Age at least. For example, artefacts found in northern German river valleys include fishhooks made from bones and teeth as well as early spears with barbed hooks. But fish is more than just a food. In many cultures the fish is raised to near-mythical status. The Maori people call New Zealand’s North Island Te-Ika-a-Maui – “the fish of Maui”. According to legend the demigod Maui pulled a mighty fish out of the water, which then transformed into the island.

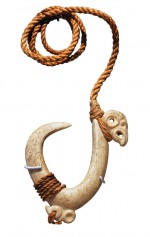

2.1 > A traditional fishhook from New Zealand.

2.1 > A traditional fishhook from New Zealand.- In the days of Alexander the Great, inhabitants of the Mediterranean town of Ascalon were such devout worshippers of the goddess Derketo, a mermaid-like being, that eating fish was taboo. The Christians even elevated the fish to a symbol of their faith community. They used the Greek word for fish, ichthys, as an acronym. It stands for Iesous Christós Theoú Hyiós Sõtér (Jesus Christ God’s Son Saviour).

Today there is little remaining sign of mythical veneration. Fish is a foodstuff and a straightforward trade commodity. According to estimates by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), today a total of 660 to 820 million people are directly or indirectly dependent on fishery. These include the families of fishermen and of their suppliers – the makers of fishing equipment, for instance. The FAO estimates the number of fishermen per se at around 54 million, of which 87 per cent live in Asia alone. Many of them work in small fisheries, and fish production per person is correspondingly low. On average it amounts to just about 1.5 tonnes. For comparison, the figure in Europe is around 25 tonnes per person.

- 2.2 > The Maori demigod Maui catches a fish, which transforms into the North Island of New Zealand, Te-Ika-a-Maui.

Large-scale versus small-scale?

Experts differentiate roughly between industrial fishery, which operates with factory ships, and artisanal fishery. Beyond this, different countries break the industry down into various other categories. In Germany and other European countries, for example, fisheries are subdivided into the following three fleet segments:- Small-scale coastal fishery: carried on with small motorboats which usually put out to sea for a day at a time. The home and landing ports are generally found in smaller coastal locations.

- Small-scale offshore fishery: makes use of vessels between 18 and 40 metres in size. The boats stay at sea for several days and land mainly fresh fish in large ports.

- Large-scale offshore fishery: ships are usually more than 40 metres long and do not necessarily stay within EU territorial waters. Catches are frozen immediately on board and sold throughout the world.

2.3 >Mass processing: Pangasius is filleted in Vietnam for export to Europe.

2.3 >Mass processing: Pangasius is filleted in Vietnam for export to Europe.- To take another example: in Mauritania, West Africa, distinctions are made between the following types of fishery:

- Small-scale fishery: includes vessels under 14 metres in length without any superstructure (wheelhouse). In many cases these are wooden boats, which may be powered by sails or motors.

- Coastal fishery: covers unmotorized vessels between 14 and 26 metres in length as well as motorized vessels with a superstructure but under 26 metres long.

- Industrial fishery: includes all larger ships that do not fit into the first two categories. Mauritania has its own industrial fleet that exclusively catches octopus. It is mainly made up of trawlers of Chinese origin, which are old and in poor technical condition.

- 2.4 > The industrialization of fishery raises per-capita production. It is still low in Asia compared to Europe. Intensive feeding and feed optimization means that productivity in aquaculture is higher than in capture fisheries. The figures for North America are probably too high.

- Like Mauritania, many developing or newly-industrializing countries have an old ocean-going fleet – if they have one at all. Offshore fisheries in the latter countries are mainly operated by factory ships based in other countries, which pay licence revenue to the State. This industrially operated fishery is often held up as exploitative in comparison to original artisanal-fishery practices. But it is important not to generalize. There is barely any market in Europe for small pelagic fish, which are mainly fished by Dutch operators in Mauritanian waters and deep-frozen on board. The small fish are only marketed in preserved form, packed in cans or jars. In contrast, the pelagic fish caught off West Africa are largely sold directly in African countries. In many places the deep-frozen fish are hacked out of their blocks of ice in the marketplace itself. In other countries like Senegal, on the other hand, governments issue too many catch-licences to foreign fleets. As a result the fish stocks are overfished. Local coastal fishers rightly fear for their income source. During the apartheid era the Namibian waters were severely overfished by foreign fishing fleets. This exploitation led to the collapse of the sardine fishery in the 1970s and subsequent closure of the mostly South African owned canneries and reduction plants. After independence in 1990, the Namibian Government focused on developing what was hitherto a small local hake fishery into a fishing industry with state of the art processing plants serving global markets. This was quite an ambitious goal considering that Namibia was a country with only limited fishing tradition. Nowadays Namibia’s innovative fisheries policy aims towards sustainable exploitation of the fishery and equitable distribution of the benefits among the Namibian population. Nonetheless, catch limits exceed scientific recommendations and foreign involvement in the fishery remains a concern as social, economic and ecological goals are in conflict on the political stage.

How “small fry” die out

The threat posed by industrial fishery to the livelihoods of artisanal fishermen is not just a developing-country phenomenon. In many industrialized countries, too, smaller family-run fishing businesses have had to give up. In many cases, no successors could be persuaded to take on this hard work. Small businesses were also squeezed by rising fuel costs, so that fishery was often taken over by larger and more efficient operations. Off the east coast of Canada, the overfishing of cod was to blame for driving hundreds of small family businesses into closure in the early 1990s. Coastal fishermen had long warned that fish were becoming scarcer, in Canadian ocean bays for instance. Nevertheless, the large companies with their industrial trawlers continued to fish further out at sea. Their argument was that coastal fish and the offshore fish stocks had nothing to do with each other.

- 2.5 > Europe, the USA and Japan are the most important importers of fish and fishery products worldwide. China is the main exporter. Norway’s position as the second largest exporter is primarily because the country exports especially valuable fish such as salmon.

- Today we know that this argument was based on false assumptions. In reality they all belonged to a single, large fish population, which was finally definitively overfished at the end of the 1980s. The coastal fishermen lost their livelihoods. Some switched to lobster fishing. Unknown numbers were uprooted and moved away. As a consequence of this rural exodus, the population slumped dramatically in many places along Canada’s east coast. The situation of herring fishers on the North Sea was similar. In the 1970s, officials reacted to the collapse of the stock with a fishing ban lasting several years. This enabled herring stocks to recover, but many family businesses did not survive the enforced interruption. Today that fishery is dominated by a few large companies. In order to avoid such drastic consequences for the people affected, social scientists are urging that more attention be given to sociological aspects in fishery management, rather than concentrating solely on the conservation of fish stocks and the marine environment. They criticize the way that so far, experts from the different disciplines – biology, economics and sociology – seem to collaborate far too seldom. Of course, the sociological approach is labour-intensive and costly, say researchers, because it requires field researchers to travel to coastal regions in order to interview the people affected, the fishermen, in situ and to analyse their situation. Yet this could avert future problems or help to solve them more quickly.

- 2.6 > For many developing countries, fish exports are more important than the coffee and cocoa trade.

The responsibility of industrialized countries

In recent years, jobs in fisheries in the European countries have undergone varying degrees of decline. Particularly because there is a shortage of alternative jobs, nations like Portugal and Spain continue to maintain large fishing fleets, often kept alive by state subsidies. Denmark and Germany, on the other hand, have drastically reduced the size of their fleets. In these countries the demand for fish, which has risen in recent years, is increasingly met by means of imports.

Today Europe is the world’s most important fish-importing region but the demand for fish varies enormously from one country to another. In 2010 Europe imported fish to the value of 44.6 billion US dollars, around 40 per cent of the worldwide trading volume. The second largest importer is the USA, with Japan in third place. Hence a special role falls to these three regions in the conservation of global fish stocks: consumers in these industrialized countries should make a stand and demand more produce from sustainable fisheries and environmentally sound aquaculture. For wholesale purchasers, in turn, labour conditions in the countries of production are beginning to matter more when they choose their suppliers. Workers in developing and newly-industrializing countries are still often underpaid and receive no social security benefits. Moreover, child labour is often used in these countries, according to FAO data. Children are put to work particularly in artisanal fishery and small family businesses, but it happens on board ships as well. They are also being used as cheap labour to repair nets, to sell fish or to feed and harvest farmed fish. All these problems have now been recognized. It is to be hoped that the first projects and initiatives currently being embarked upon as good examples will set a precedent for the future.