Legal issues in marine medical research

What makes the substances so interesting

Interest in the genetic resources found on the deep seabed has increased dramatically in recent years. They include microorganisms which occur in enormous quantities around hydrothermal vent sites, known as black smokers (Chapter 7) on the ocean floor. In complete darkness the microorganisms produce biomass from carbon dioxide and water. The energy they need for the conversion of carbon dioxide is extracted/obtained from the oxidation of hydrogen sulphide that discharges from the sea floor via the black smokers. Experts call this type of biomass production “chemosynthesis”. In contrast, plants produce biomass by photosynthesis, which is driven by energy-rich sunlight.

Chemosynthetic bacteria are of great interest, as they possess unique genetic structures and special biochemical agents which could play a key role in developing effective vaccines and antibiotics, or in cancer research. It would also appear desirable from the industrial sectors point of view to exploit these organisms. After all, the bacteria which are active at the black smokers can tolerate high water pressures and extreme temperatures. Heat-stable enzymes have now been isolated from these resilient extremophilic bacteria and could potentially be used by industry. For instance, many manufacturing processes in the food and cosmetic industries operate at high temperatures, and heat-resistant enzymes would greatly simplify these. The ability to convert and thus detoxify deadly poisonous hydrogen sulphide into more benign sulphur compounds makes the chemosynthetic bacteria even more attractive.

Who “owns” the marine substances?

Against this background, one key question arises: who has the right to utilize and research the genetic resources of the deep seabed? International law initially differentiates only according to country of origin. If a scientific research institute applies to collect samples of deep sea organisms during an expedition, its activities are attributed to the flag state of the research vessel. Alternatively, the country of origin of the syndicate or biotechnology enterprise involved is the determining factor. Where the sample microbes are to be taken from is also relevant. According to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) (Chapter 10), marine scientific research in the exclusive economic zone generally requires the consent of the coastal state. Provided these are required purely for research purposes, the coastal state should allow third countries to take samples from the waters over which it exercises jurisdiction. In the event that the research findings could ultimately have commercial potential (bio-prospecting), the coastal state may exercise its own discretion. In case of doubt it may withhold its consent to the conduct of the activities in its waters. This applies particularly to measures which are of direct economic significance, such as the exploration of natural resources: in other words, exploring the seabed with the intention of exploiting its resources.

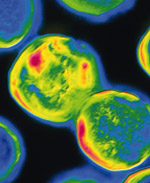

9.14 > Some microbes, e.g. the single-celled archaea, live in the vicinity of hot springs. Some contain substances which lend themselves to industrial production. Certain marine bacteria can be used to manufacture polymers, special synthetics which could even be utilized for future cancer therapy.

9.14 > Some microbes, e.g. the single-celled archaea, live in the vicinity of hot springs. Some contain substances which lend themselves to industrial production. Certain marine bacteria can be used to manufacture polymers, special synthetics which could even be utilized for future cancer therapy. In the case of maritime regions beyond the limits of national jurisdiction, the legal situation is less clear-cut. Who has the right to exploit the biological resources of the high seas, and the legal provisions that should govern such activity, have long been matters of dispute within the international community. This includes those areas far from the coast where the black smokers are to be found, such as the mid-ocean ridges. The problem is that none of the international conventions and agreements contains clear provisions on the exploitation of genetic resources on the ocean floor. For this reason one section of the international community considers that they should be fairly shared between nations. The other, however, believes that any nation should have free access to these resources. Clearly, these views are diametrically opposed.

In the case of maritime regions beyond the limits of national jurisdiction, the legal situation is less clear-cut. Who has the right to exploit the biological resources of the high seas, and the legal provisions that should govern such activity, have long been matters of dispute within the international community. This includes those areas far from the coast where the black smokers are to be found, such as the mid-ocean ridges. The problem is that none of the international conventions and agreements contains clear provisions on the exploitation of genetic resources on the ocean floor. For this reason one section of the international community considers that they should be fairly shared between nations. The other, however, believes that any nation should have free access to these resources. Clearly, these views are diametrically opposed.

- With regard to the deep seabed, the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) stipulates that “the area of the seabed ... beyond the limits of national jurisdiction, as well as its resources, are the common heritage of mankind”. But this provision applies only to mineral resources such as ores and manganese nodules. If a state wishes to exploit manganese nodules on the deep seabed (Chapter 10), it must obtain a licence from the International Seabed Authority (ISA) and share the benefits with the developing countries. This explicit provision does not apply to genetic resources on the deep sea floor, however.

On the other hand, the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) adopted in Rio de Janeiro in 1992 calls for “the fair and equitable sharing of the benefits arising out of the utilization of genetic resources”; in other words, nature’s biological bounty should be shared fairly between the industrialized nations and the developing countries. However, this objective refers only to the area within the limits of national jurisdiction and not to maritime regions far from land.

- So the situation remains unresolved, with each side interpreting the content of UNCLOS and the Convention on Biological Diversity according to its own best interests. The situation is further complicated by UNCLOS allowing yet another interpretation. It establishes the “freedom of the high seas”, under which all nations are free to utilize resources and carry out research at will. This includes the right to engage in fishing in international waters. All states are entitled to take measures for “the conservation and management of the living resources of the high seas”. As the regime of the high seas under UNCLOS also covers the deep seabed and to the extent to which the convention does not contain any special rule to the contrary, this implies that the biological and genetic resources there are no less freely available than the fish. As a result all nations should be at liberty to research and utilize the genetic resources found on the deep seabed. This opinion is shared by most members of a special United Nations working group set up by the United Nations General Assembly in 2005 to address the protection and sustainable use of marine biodiversity beyond national jurisdiction.

- 9.15 > Regulation of the exploitation of genetic resources on the seabed bed has so far proved inadequate. A state may withhold consent within its EEZ. There are no clear guidelines governing international waters, which can lead to conflict between states.

- Other members of the UN working group are opposed to this interpretation. As mentioned above, they want the biological resources – similar to minerals – to be shared equally between the individual states. The impasse has triggered heated debate at international meetings of the UN working group, and agreement is not expected any time soon. It is likely that at least one of the two conventions would need to be amended, and there is little chance of this happening at present.

There could be another solution, however. Some experts argue that neither UNCLOS nor the Convention on Biodiversity should primarily apply to genetic resources. Ultimately this is not about harvesting resources such as fish, minerals or ores from the seabed. It is about searching for substances in a few organisms, using these substances to develop new drugs and, later, manufacturing the drugs in industrial facilities. Strictly speaking, therefore, it is the information itself contained in the ocean organisms which is of interest, not the organisms themselves. Arguably this is more an issue of intellectual property than the traditional exploitation of natural resources – indicating that patent law would most closely fit. There is a lot to be said, therefore, for leaving international marine and environmental law as it stands, and liberalizing the provisions of international patent protection.

- 9.16 > National and international patent law governs the exploitation of natural resources and genetic information from living organisms. Substances extracted from organisms are patentable. The same applies to individual isolated gene sequences and genetically modified organisms. Newly-discovered species of animal and all their genetic material, however, cannot be patented.

-

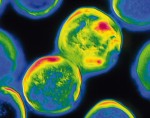

9.17 > Heat-loving, extremophilic bacteria Archaeoglobus fulgidus live around hot springs on the ocean floor and thrive in ambient temperatures of about 80 degrees Celsius.

9.17 > Heat-loving, extremophilic bacteria Archaeoglobus fulgidus live around hot springs on the ocean floor and thrive in ambient temperatures of about 80 degrees Celsius. The limits to patent law

If the search for marine substances touches on legal issues, then it is important to settle the question of how the research findings may be commercially utilized and exploited. In principle, patent protection of utilization and exploitation rights is governed by the provisions of domestic law. In Germany these are anchored in the Patent Act (PatG). In general this Act protects inventions, including findings from genetic research. The protection afforded by this Act ends at Germany’s national borders. International protection of intellectual property is provided by the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS), which applies within the sphere of influence of the World Trade Organization (WTO). The TRIPS agreement provides for mutual recognition of intellectual property rights by the signatories provided that these rights are protected by national patents. The intellectual property of all TRIPS signatories is thus protected.

Patentable objects basically include any microorganisms, animals or plants modified in the laboratory, such as genetically-modified varieties of maize. They may also be elements isolated from the human body or otherwise produced by means of a technical process, especially living cells, including the sequence or partial sequence of a gene. The discovery of a new species, however, is not patentable as a species cannot be patented as a matter of principle. On the other hand, biological material found in nature or the genetic code can be considered new in terms of patentability if it is isolated by a technical process and, by written description, is made available for the first time. Every state has the right to exclude from patentability animals, plants and the biological processes used to breed them – such as new breeds of animals, as has occurred in Germany with the Patent Act and in the EU with the Biopatent Directive. The same applies to other inventions and individual DNA sequences where economic exploitation is to be prevented for reasons of ethics and security, such as the cloning of human embryos.

- According to the TRIPS Agreement, commercial exploitation may be prevented when, in the opinion of the state concerned, this is necessary for the protection of “ordre public or morality; this explicitly includes inventions dangerous to human, animal or plant life or health or seriously prejudicial to the environment”. According to the Biopatent Directive adopted by the EU in 1998, inventions are not patentable if their commercial exploitation may offend against ordre public or morality. This includes processes for cloning human beings and uses of human embryos for industrial or commercial purposes.

- The different institutions are divided on the question of how far patent protection of DNA sequences should go. In the EU, protection is limited to the functions of the sequence or partial sequence of any gene described in the patent application. In contrast, in the USA the principle of absolute protection applies, without limitation to the functions described by the inventor. This means that in the USA not only the invention explicitly described in the application is protected by patent law, but also any developments and products which may follow in future. US patent law is therefore much more comprehensive than its European counterpart, but both approaches are compatible with international provisions. The different concepts constantly lead to controversy. The level of protection afforded by patent law to marine-derived drugs, too, will vary from region to region. This situation is unlikely to change in the near future. Behind this argument lie historic and cultural differences in concepts of individual freedom and a government’s duty to protect.