Sea-level rise – an unavoidable threat

Loss of habitats and cultural treasures

Sea-level rise is one of the most serious consequences of global warming. No one can really imagine how the coasts will look if the waters rise by several metres over the course of a few centuries. Coastal areas are among the most densely populated regions of the worldCoastal areas are among the most densely populated regions of the worldand are therefore particularly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. They include major agricultural zones, conurbations and heritage sites. How will climate change affect their appearance?Further information on this topic is available here:

Researchers around the world are seeking answers to the question of how rapidly, and to what extent, sea level will rise as a consequence of climate change. In doing so, they must take account of the fact that sea level is affected not only by the human-induced greenhouse effect but also by natural processes. Experts make a distinction between:- eustatic causes: this refers to climate-related climate-relatedglobal changes due to water mass being added to the oceans. The sea-level rise following the melting of large glaciers at the end of ice ages is an example of eustatic sea-level rise;Further information on this topic is available here:

- isostatic (generally tectonic) causes: these mainly have regional effects. The ice sheets formed during the ice ages are one example. Due to their great weight, they cause the Earth’s crust in certain regions to sink, they cause the Earth’s crust in certain regions to sink,so sea level rises relative to the land. If the ice melts, the land mass rises once more. This phenomenon can still be observed on the Scandinavian land mass today.Further information on this topic is available here:

- eustatic causes: this refers to climate-related

3.1 > Until 6000 years ago, sea level rose at an average rate of approximately 80 cm per century, with occasional sharp increases. There were at least two periods, each lasting around 300 years, when sea level rose by 5 metres per century. This was caused by meltwater pulses.

3.1 > Until 6000 years ago, sea level rose at an average rate of approximately 80 cm per century, with occasional sharp increases. There were at least two periods, each lasting around 300 years, when sea level rose by 5 metres per century. This was caused by meltwater pulses.- Sea level can change by 10 metres or so within the course of a few centuries and can certainly fluctuate by more than 200 metres over millions of years. Over the last 3 million years, the frequency and intensity of these fluctuations increased due to the ice ages: during the colder (glacial) periods, large continental ice sheets formed at higher latitudes, withdrawing water from the oceans, and sea level decreased dramatically all over the world. During the warmer (interglacial) periods, the continental ice caps melted and sea level rose substantially again.

The last warmer (interglacial) period comparable with the current climatic period occurred between 130,000 and 118,000 years ago. At that time, sea level was 4 to 6 metres higher than it is today. This was followed by an irregular transition into the last colder (glacial) period, with the Earth experiencing its Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) 26,000 to 20,000 years ago. At that time, sea level was 121 to 125 metres lower than it is today. Then the next warmer period began and sea level rose at a relatively even rate. There were, however, intermittent periods of more rapid rise triggered by meltwater pulses. These were caused by calving of large ice masses in the Antarctic and in the glacial regions of the Northern hemisphere, or, in some cases, by overflow from massive natural reservoirs which had been formed by meltwater from retreating inland glaciers. This relatively strong sea-level rise continued until around 6000 years ago. Since then, sea level has remained largely unchanged, apart from minor fluctuations amounting to a few centimetres per century.

- 3.2 > Every time there is a storm, the North Sea continues its relentless erosion of the coast near the small English town of Happisburgh. The old coastal defences are largely ineffective. Here, a Second World War bunker has fallen from the eroded cliffs, while elsewhere along the coast, homes have already been lost to the sea.

-

Sea-level rise Sea-level rise has various causes. Eustatic rise results from the melting of glaciers and the discharge of these water masses into the sea. Isostatic rise, on the other hand, is caused by tectonic shifts such as the rise and fall of the Earth’s crustal plates. Thermal expansion, in turn, is caused by the expansion of seawater due to global warming.

- Measured against the minor changes occurring over the last 6000 years, the global sea-level rise of 18 cm over the course of the last century is considerable. Over the past decade alone, sea level rose by 3.2 cm, according to measurements taken along the coast in the last century and, since 1993, satellite monitoring of the elevation of land and water surfaces worldwide (satellite altimetry). Admittedly, these are only short periods of time, but the measurements nonetheless point to a substantial increase in the rate of sea-level rise. Experts differ in their opinions about the extent to which specific factors play a role here:

- Between 15 and 50 per cent of sea-level rise is attributed to the temperature-related expansion of seawater;

- Between 25 and 45 per cent is thought to be caused by the melting of mountain glaciers outside the polar regions;

- Between 15 and 40 per cent is ascribed to the melting of the Greenland and Antarctic ice caps.

3.3 > Tourists preparing to abseil off the edge of the Ross Ice Shelf in Antarctica. Greater melting of the mass of floating ice that forms ice shelves could result in an increase in the calving rate of glaciers if the ice shelf is no longer there to act as a barrier.

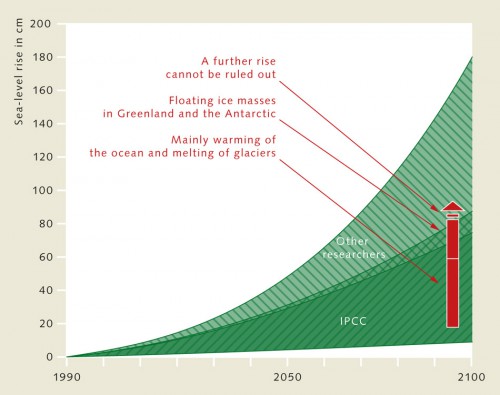

3.3 > Tourists preparing to abseil off the edge of the Ross Ice Shelf in Antarctica. Greater melting of the mass of floating ice that forms ice shelves could result in an increase in the calving rate of glaciers if the ice shelf is no longer there to act as a barrier.- Based on the monitoring data and using computer modelling, predictions can be made about future sea-level rise, such as those contained in the latest Report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC, 2007). This is the most up-to-date global climate report currently availablethe most up-to-date global climate report currently available, and it forecasts a global sea-level rise of up to 59 cm by 2100. This does not take into account that the large continental ice masses (i.e. primarily the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets) could melt more rapidly as a result of global warming. In fact, current satellite monitoring around the edges of the Greenland ice sheet, West Antarctica and the mountain glaciers outside the polar regions shows that the height of the glaciers and hence the volume of ice are decreasing faster than experts had previously assumed. These data and computer modelling suggest that sea level could actually rise by more than 80 cm, and perhaps even by as much as 180 cm by the end of this century. The melting of the Antarctic and Greenland glaciers is likely to intensify well into the next century and beyond. The other mountain glaciers will already have melted away by then and will no longer contribute to sea-level rise.Further information on this topic is available here:

The German Advisory Council on Global Change (WBGU) expects a sea-level rise of 2.5 to 5.1 metres by 2300. The reason for the considerable divergence in these figures is that the climate system is sluggish and does not change at an even or linear rate, so forecasts are beset with uncertainties. What is certain is that the sea-level rise will accelerate slowly at first. Based on the current rate of increase, sea level would rise by just under 1 metre by 2300.

The present rise is a reaction to the average global warming of just 0.7 degrees Celsius over the past 30 years. However, the IPCC Report forecasts a far greater temperature increase of 2 to 3 degrees Celsius in future. This could produce a sea-level rise at some point in the future that matches the level predicted by the German Advisory Council on Global Change.

- 3.4 > Sea level will rise significantly by the end of this century, although the precise extent to which it will rise is unclear. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) forecasts a rise of up to 1 metre during this century (dark green shading above). Other researchers consider that a rise of as much as 180 cm is possible (light green shading above). As there are numerous studies and scenarios numerous studies and scenariosto back up both these projections, the findings and figures cover a broad range. There will certainly be feedback effects between the melting of the glaciers and the expansion of water due to global warming. Record rates of sea-level rise are predicted in the event of more rapid melting of the Antarctic and Greenland ice sheets.Further information on this topic is available here:

- As with all climate fluctuations that have occurred in the Earth’s recent history, the global warming now taking place will increase temperatures in the polar regions more strongly than the global mean and will therefore significantly influence sea-level rise. The stronger warming at higher latitudes is caused by the decrease in albedo, i.e. the surface reflectivity of the sun’s radiation: as the light-coloured, highly reflective areas of sea ice and glaciers shrink, more dark-coloured soil and sea surfaces are revealed, which absorb sunlight to a far greater extent. If most of the continental ice sheets in Greenland and West Antarctica melt, sea level could increase by as much as 20 metres over the course of 1000 years in a worst-case scenario.

In West Antarctica in particular, the marginal glaciers are becoming unstable as a result of flow effects, and are exerting pressure on the ice shelves floating on the sea. This could result in the ice shelf breaking away from the grounded ice to which it is attached, which rests on bedrock and feeds the ice shelf. This would ultimately result in the glaciers calving, as the ice shelf would no longer be there to act as a barrier. Furthermore, even with only a slight sea-level rise, marginal grounded ice masses could break away in significant amounts due to constant underwashing by the rising water.