Towards better fisheries management

Conflict over a living resource

The importance of establishing clear regulatory arrangements for fishing activity was demonstrated with particularly dramatic effect by the Cod Wars in the Northeast Atlantic in the 1950s and 1970s. At the time, many foreign trawlers used to fish close to the Icelandic coast, for unlike today, there was no exclusive economic zone (EEZ) extending 200 nautical miles out from the coastal baseline. This led to a conflict over access to fish stocks, mainly between Iceland and Great Britain. At the peak of the conflict in 1975/1976, Britain even sent in warships. The situation was not defused until 1982, when the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) was adopted, establishing exclusive economic zones.

This example shows the high level of demand for fish, a lucrative and highly tradable commodity. It also shows how serious the consequences of a poorly regulated fishery can be. Even today, there are periodic conflicts between countries over fishing rights or the allocation of fishing quotas. A much greater challenge at present, however, is the overexploited status of many stocks. The primary task of modern fisheries management is therefore to limit catch volumes to a biologically and economically sustainable level and ensure equitable access to fish as a living resource.

- 5.9 > A scene from the Cod Wars: the Icelandic vessel “Ver” (left) attempts to cut the fishing lines of the British trawler “Northern Reward” (right). The British tugboat “Statesman” intervenes.

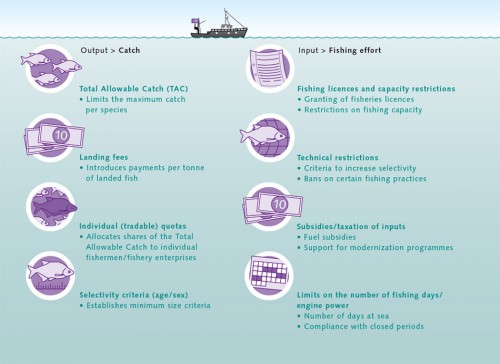

- Fisheries policy or centralized fisheries management therefore focuses either on catch volumes (direct approach) or fishing effort (indirect approach):

- Fishing volume: To prevent too many fish being caught, the authorities can limit catch volumes (output). In most cases, this means setting a total allow-able catch (TAC). This defines the maximum quantity of a given species that may be caught in a specific area, generally the EEZ, in any year.

- Fishing effort: To prevent too many fish being caught, the authorities can also limit fishing effort (input). For example, their effort-based management measures can include limiting the number of fishing days, fishing vessels’ engine power, or the size of the fleet, or setting minimum mesh size for nets.

Fishing quotas – equal rights for all?

In fact, it is quite possible to regulate fishing effectively with the aid of fishing quotas. To that end, a total allow-able catch (TAC) is set for a specific marine area. The TAC is then broken down into separate national fishing quotas for the various countries which border this maritime region. For example, each Baltic Sea state has a national fishing quota. Of course, for this system to function effectively, more is required than a single national quota: otherwise, fishermen within a single country would find themselves in direct competition with each other and would attempt to catch as many fish as possible at the start of the season in order to fulfil a large share of the quota. This would lead to a glut of fish on the market for a short period, pushing down prices and ultimately harming the fishermen’s livelihoods.

So in order to give fishermen a measure of security to plan their fishing activities for the entire season, the total allowable catch is generally allocated to individual fishing vessels, fishermen or cooperatives. Fisheries policy strategies in which fishermen are allocated long-term fishing rights in some form are known as rights-based fisheries management. Individual transferable quotas (ITQs) are the prime example.

- 5.10 > Classic approaches to fisheries management either focus on restricting catches or attempt to limit fishing effort. The term “fisheries management” encompasses a variety of methods which can be used to regulate the fishing industry. Their suitability in any given context depends on the fish stock and region.

- In an ITQ system, fishermen are allocated individual fishing quotas as a percentage share of the total allowable catch. As a rule, the ITQs are allocated for a period of several years, giving the fishermen the stability they need to plan ahead. The fishermen can trade their ITQs freely with other fishermen, which often results in relatively unprofitable enterprises selling their quotas to more efficient companies. Less economically efficient companies would be inclined to sell, and more profitable companies would be likely to buy the ITQs. The main goal of the ITQs is to achieve the greatest possible economic efficiency and sustainability. There is less focus on social objectives. In extreme cases, the quotas become concentrated in the hands of a small number of companies.

One example is the New Zealand hoki fishery, which is now dominated almost completely by a small number of large fishery enterprises.

Another example is the Icelandic fishery. The management of Iceland’s cod stocks is considered to be fairly good nowadays as regards sustainability. Following the introduction of ITQs, however, many family-owned companies left the fishing industry and sold their quotas to other enterprises.

ITQs are traded like stocks and shares. High ITQ prices are therefore an indicator of good fisheries management: the higher the yield from the fish stock, the more valuable the fishing rights become. In Iceland, fishing rights were initially distributed free of charge to the fishermen based on their average catches at the time (grandfather rights). In other words, rights of access to this natural resource were allocated on the basis of historic fishing privileges, which in some cases go back many generations. As fisheries management has steadily improved, however, and fishing fleets became more efficient as a result of the rationalization measures described, the fishing rights – which are now very valuable – have become concentrated in the hands of a small number of enterprises.

- In Iceland, this development is viewed very critically. The preferred situation is more equitable distribution of profits from fishing. Some experts are therefore proposing that rather than granting permanent fishing rights, annual quotas should be auctioned instead. The advantage of this system, it is argued, is that smaller or recently established fishing companies could enter the trading scheme and acquire quotas at any time, without having to hand over extremely large sums of money.

There are frequent demands at political level for small-scale coastal fishing to be protected, prompting calls for separate quotas to be allocated on the basis of fleet segment. This would mean that quotas allocated to small vessels could only be sold on to other small vessel owners and could not be used to increase a large vessel’s fishing quota. The expert view is that the ITQs are an effective tool for the management of fisheries, but as soon as social goals come into play, it is essential to rethink the basic principles.

- 5.12 > Hot competi-tion for limited resources: in Sitka Sound in Alaska, the herring fishery is only open for a few hours a year. Dozens of boats then compete for the catch.

Effort-based management – fewer days, fewer ships

In addition to the use of quotas, fishing can also be regulated by restricting the fishing effort. For example, fishing capacity can be limited by capping the number of licences available for allocation to fishing vessels or by restricting the engine power or size of vessels. It is also possible to limit the duration of fishing, e.g. by capping the number of days that may be spent at sea. These restrictions on fishing effort are more common than ITQ schemes in some regions. However, effort-based management also has its shortcomings and is sometimes taken to absurd extremes by fishermen themselves. One example is the Pacific halibut fishery, where at the end of the 1980s, fishing was only permitted for three days a year in order to conserve stocks.

In practice, during this very short fishing season, a vast fishing fleet was deployed and caught the same quantity of fish as had previously been harvested in an entire year. Another even more extreme example of a time limit is the fishing derby in Sitka Sound in the Gulf of Alaska. Here, the herring fishery is regulated by limiting fishing activity to a few hours a year. Rather like a horse race, all the fishing vessels line up and, as soon as they hear the signal, they set off at the same time. While fishing is monitored by an observer ship, the fishermen try to catch as much fish as possible in the very short time available. After a few hours, another signal tells the fishermen that it is time to stop fishing.

Selective fishing with the aid of electric nets and LED lights

Various types of fishing gear are utilised, depending on the species or habitat. Bottom-living species are caught using bottom trawls, whereas fish living in open waters are caught using pelagic nets. Steel long-lines – carrying hundreds of thin lines and baited hooks – are often used to catch tuna.

Some of these fishing techniques have considerable disadvantages. A prime example is the beam trawl, a type of net that is dragged across the seabed. Beam trawls are often equipped with iron chains that disturb the flatfish on the seabed and drive them into the net. The beam trawl is the subject of considerable controversy because it ploughs its way along the seabed and destroys numerous bottom-living creatures.

Long-lines, in turn, are notorious for their bycatch harvest of dolphins and turtles, which are attracted by the bait on the hooks. Seabirds such as albatross are also frequent casualties: they dive for the bait when the lines are thrown from the ship into the water and are briefly suspended near the surface. Over recent years, various alternative and gentler fishing techniques have therefore been developed:- the Danish seine, a specific form of towed net. Conventional trawl nets are generally equipped with weights to help them sink. However, these weights can kill other marine fauna or damage sensitive seabed habitats. With a Danish seine, contact with the seabed is minimized due to its specific geometric structure, consisting of diamond knotted netting turned 90° from its usual orientation;

- pelagic trawl nets with escape hatches for turtles;

- long-lines with additional lead weights that cause the lines to sink rapidly, taking them out of seabirds’ reach;

- unusually shaped hooks for long-lines that avoid turtle bycatch;

- electric fishing nets which produce a mild electric pulse to disturb the flatfish and drive them into the net, instead of using heavy chains (tickler chains) for this purpose;

- gillnets equipped with fishing lights (LED markers or lightsticks), which scare away turtles or alert them to the presence of the net.

Extra Info Different fishing techniques and their impacts on the environment.

- For some years, the development of gentler (i.e. more selective) fishing technologies has been promoted by an international environmental organization through the Smart Gear initiative. It is noteworthy that it is not only researchers and engineers who are involved in the initiative; so too are professional fishermen. The many different solutions offer hope that gentler forms of fishing will come to the fore. Many fishermen, especially in Northern Europe, have already switched from beam trawling to alternative fishing techniques for pragmatic reasons. With rising oil prices, dragging a heavy beam trawl along the seabed is no longer economically viable. In many areas, lighter fishing gear such as Danish seines is being used instead.

Generally speaking, effort-based management must be constantly adapted to the latest technological advances. Increasingly efficient technology is available to locate fish, for example, making it possible to detect and catch a given amount of fish in ever shorter periods of time. Experts estimate that industrial fishing is achieving a 3 per cent increase in efficiency year on year, so fishing effort must be reduced.

Another way of protecting fish stocks is to establish designated marine protected areas, where fishing is restricted or subject to a total ban. In some areas, bottom trawling, for example, is prohibited altogether in order to protect seabed habitats. In other cases, specific areas are protected, notably those where fish come to spawn and juveniles grow to maturity. This approach can only be successful, however, if very accurate information is available about the whereabouts and reproduction habits of fish or marine fauna in relation to the protected areas. Furthermore, a protected area must be the right size. If it is too small, the stock will not be adequately protected. If it is too large, the fishermen will lose access to stocks that they could in fact catch without putting stocks at risk.Sustainable, high-yield fishing is possible

Despite the numerous problems, well-organized fisheries management can work, as the examples of Alaska, Australia and New Zealand show. Most stocks in these regions are fished sustainably and are in a good state. In many cases, TACs and ITQs have been set in accordance with the maximum sustainable yield (MSY) principle, i.e. the maximum annual catch that can be taken from a species’ stock over an indefinite period without jeopardizing that stock.

In some fisheries, the limit reference points and target reference points for the maximum annual catch are even more stringent than the MSY. The following factors contribute to successful fisheries management:- The fishing industry and policy-makers comply with researchers’ recommendations on catch volumes and with limit reference points and target reference points.

- Various interest groups are involved in the management process at an early stage. Researchers’ expertise plays a key role in the setting of quotas. In addition to commercial fishing companies, recreational fishing associations and non-government organizations are involved in the allocation of fishing rights, in measures to avoid bycatch, and in other aspects of fisheries management.

- Responsibilities for the various aspects of fisheries management are clearly defined and hierarchically structured. Fishing in international waters is regulated by one of the Regional Fisheries Management Organizations (RFMOs). Fishing in the exclusive economic zone is managed by national authorities, while fishing in coastal waters falls within the jurisdiction of local authorities.

- Government observers are deployed and their operating costs are covered by the fishery enterprises, generating funds for the research community. The entire Alaska pollock (Theragra chalcogramma) fishery, for example, is monitored by onboard observers. Landings in port are also monitored by CCTV.

- The focus is not only on individual fish species: efforts are also made to manage fishing in a way which protects the ecosystem as a whole. Experts call this the ecosystem approach. Among other things, it means that no heavy fishing gear can be used that would potentially damage the seabed.

- The management authorities are willing to learn from others’ mistakes and, from the outset, target their measures towards avoiding overfishing. This is the case in both Alaska and New Zealand, where industrial fishing began only around 20 years ago.

- In the USA, the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act adopted in 1976 contains the main legal provisions applicable to fishing. The Act has been revised several times over the years, most recently in 2007. The latest amendments introduce measures for the USA as a whole which are very much in line with some of those already in place in Alaska. For example, fishing should now take greater account of environmental conservation aspects and protect important fish habitats. The objectives defined in the Act are to be achieved with the aid of fishery management plans (FMPs) which incorporate the economic, ecological and social dimensions. Although there is some opposition to these stringent rules in the USA, they are now established in law and non-governmental organizations can bring legal actions in the event of violations.

The right management regime for each stock

So which management measures are most appropriate to generate a high but sustainable yield over the long term while protecting fish stocks and marine habitats? This will ultimately depend on the fish stock and the local situation. In industrial fishing, which is carried out using vast vessels and provides employment for around 500,000 fishermen worldwide, the fishing activity could, in theory, be monitored by onboard observers, although this is associated with high costs. However, in countries where artisanal fishing involving hundreds of small boats is the norm, as in West Africa, this type of surveillance measure cannot possibly work. With an estimated 12 million artisanal fishermen worldwide, it is quite impossible to monitor all of them at work. Nonetheless, there are some promising strategies for monitoring the catches of small and medium-sized coastal fisheries as well. In Morocco, for example, the authorities have introduced automated systems to monitor coastal fishing. Machines are installed in port or in the coastal villages and fishermen are allocated a chip card which they insert into the machines to register their departure and arrival times. This gives the authorities an ongoing overview of which particular fishermen are at sea at any given time. If a ship does not return to port on time, the authorities can run preventive checks. This system also allows fishing effort to be estimated very accurately. The catches are recorded by the authorities on landing. At present, the system is used to record vessels of trawler size, but from next year, smaller motor boats will also be monitored using this system, with spot checks on these smaller vessels’ catches also being carried out. Penalties are imposed on fishermen who provide false information about their catch. These penalties depend on the severity of the offence, but in some cases can include the confiscation and scrapping of the boat.

- 5.14 > Fishing without bycatch: stilt fishermen in Sri Lanka’s coastal waters wait patiently for their prey, which they haul out of the water with rods and landing nets.

More regional responsibility

Territorial use rights in fisheries (TURFs) are an alternative to centralized approaches to fisheries management. Here, individual users or specific user groups, such as cooperatives, are allocated a long-term and exclusive right to fish a geographically limited area of the sea. Catches and fishing effort are decided upon by the individual fishermen or user groups.

This self-organization by the private sector can also help to achieve a substantial reduction in government expenditure on regulation and control. Users also have a vested interest in ensuring that they do not overexploit the stocks, as this is necessary to safeguard their own incomes in the long term. However, a use right for a stock of fish or other living resource in the ocean is exclusive only for non-migratory species such as crustaceans and molluscs.

One example of successful management by means of TURFs is the artisanal coastal fishery in Chile, which mainly harvests bottom-living species, particularly sea urchins and oysters. Fishermen here have shown that they have a vested interest in pursuing sustainable fishing once they have the prospect of obtaining secure revenues from these fishing practices over the long term. Similar approaches are being pursued in the lobster fishery in Canada. Experts use the term “co-management” to describe this trend towards more individual responsibility for fishermen (ownership).

Economic benefits of sustainable fisheries management

Overfishing of stocks is not only an ecological problem. It is also uneconomic. As fish stocks decline, the effort required to catch a given quantity of fish increases. The fishermen spend more time at sea and use more fuel to catch a given quantity of fish. So it makes sense to manage stocks in accordance with the MSY principle. One problem is that even now, many countries are still heavily subsidizing their fishing industry. Government subsidies allow the fishery to be maintained even when the direct costs of the fishing effort, in the form of wages or fuel costs, have already exceeded the value of the fishing yield. Fishermen’s individual operating costs are reduced in many cases by direct or indirect subsidies. Every year worldwide, around 13 billion US dollars is paid to fishermen in the form of fuel subsidies or through modernization programmes, with 80 per cent of this in the industrialized countries.

Extra Info Mauritania, Senegal and the difficult path towards good fisheries management

- A recent study concludes that restructuring of subsidized fisheries would pay off because it would put an end to overfishing. Stocks would recover, leading to higher yields in future. Restructuring would mean that fishing would have to be suspended for a time or substantially reduced in certain regions. Instead of subsidizing the fishing industry, the money would be used to support fishermen who were unemployed, even if only temporarily, as a result of these measures. The great importance of social protection schemes is shown by the closure of the herring fishery in the North Sea between 1977 and 1981. Although stocks were able to recover, small coastal fishing companies did not survive this enforced break, and today, the North Sea herring fishery is dominated by a small number of major companies. However, if periods when restrictions on fishing activity are in force can be managed in a socially equitable manner and stocks recover, fishing can then be resumed. Of course, the fishing industry loses revenue as a result of the closure of a fishery or a reduction in fishing activity. However, the study concludes that this type of restructuring measure would only take around 12 years to pay for itself and would generate as much as 53 billion US dollars in additional revenue for the fishing industry annually. These calculations are very much in line with older estimated figures produced by the World Bank. It estimates the loss of net benefits due to overfishing, inefficiency and poor management to be in the order of 50 billion US dollars annually worldwide – a substantial figure compared with the total annual landed value of fish globally, i.e. around 90 billion US dollars. Admittedly, this global analysis is based on generalizations to some extent, as there are strong variations between countries’ fishing industries, but experts regard the estimated figures as sound.

- 5.17 > Generous subsidies, large fleets: the Spanish fishing fleet in particular – part of which is seen here in the port of Muros – was dependent on state subsidies for many years.

Certificates increase the appeal of sustainable fishing

Overall, the status of fish stocks worldwide still gives cause for concern. On a positive note, however, sustainable fisheries management is becoming increasingly attractive to many fishing companies. The reason is that fishing companies that fish sustainably can now market their products under an ecolabel. For many food retailers in Europe and North America, the most important importing regions worldwide, these labels are now a key prerequisite for including a given fishery product in their ranges. Various certification schemes are now in operation. Two of the best-known schemes are run by the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) and the Friend of the Sea initiative. The MSC was established by a well-known environmental organization and an international food corporation in 1997 and became fully independent in 1999. There are currently 133 MSC-certified wild capture fisheries worldwide, harvesting more than 5 million tonnes of MSC-certified fish and shellfish annually. This represents almost 6 per cent of the total global wild capture catch. The Friend of the Sea initiative was also established by an environmental organization. Both schemes aim, among other things, to support the sustainable management of fish stocks in accordance with the MSY principle.

- As a rule, certificates are granted to individual fisheries, not to individual species, and certification is contingent on compliance with various criteria. The condition of the fish stock, the impacts of fishing activity on the marine ecosystem, and the management of the fishery are all factors that are considered in the assessment. Certification to MSC standard, for example, is based on 31 separate criteria, and fisheries are required to meet a specific number of them. They include the following:

- Fishermen should utilize modern and improved fishing gear that reduces bycatch to a minimum.

- The fishing operation should implement appropriate fishing methods designed to minimize adverse impacts on habitat. For example, instead of heavy bottom trawls which churn up the seabed and destroy bottom-living fauna, rockhopper trawls should be used. These are fitted with large rubber tyres or rollers that allow the net to pass fairly easily over the seabed.

- The fishing operation should minimize operational waste such as lost fishing gear, oil spills, etc.

- The fishing operation should be conducted in areas where fisheries management systems are in place and in compliance with these systems. Areas where industrial fishing would compete with traditional coastal fishing should be avoided.

- The fishing industry should engage in intensive dialogue with scientists. Comprehensive data relating to the current status of fish stocks should be collected for use in fisheries science.

- The fishery should also prevent illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing. The certificates also state which ports are to be used. Landings are limited to a specific number of ports where there is proper monitoring of catch landings. A certificate is awarded for 5 years and can be renewed. Checks are carried out at intervals to ascertain whether the rules are being complied with. This takes the form of logbook checks and perusal of records, as well as onboard inspections. These audits may also be attended by observers from non-governmental organizations or environmental associations. Observers also travel out with the ships in order to carry out random checks to determine how much fish is being caught and from which species. In the case of the South African hake fishery, the South African Deep Sea Trawling Industry Association provides the funding for the deployment of observers. These are experts from various environmental organizations and South African ornithological associations with a particular interest in seabird bycatch. The catch is also subject to video camera surveillance. In the cod and pollock fisheries in the Barents Sea, observers commissioned by a government-funded Polar Research Institute of Marine Fisheries and Oceanography have an onboard presence on 5 per cent of all fishing expeditions. Critics argue that the certification procedures are not stringent enough as only a proportion of the criteria must be fulfilled. They claim that certificates are in some cases awarded to stocks that are in a less than optimum condition or that have not yet fully recovered. This applies to stocks with biomass growth lower than the level needed to supply a maximum sustainable yield. The critics are therefore calling for even more restrictive certification. From the certifiers’ perspective, however, ecolabelling is entirely justified, as it imposes obligations on companies to fish in a manner that enables stocks to recover. The certificate establishes clear targets and objectives for the companies, which must be achieved within a specific timeframe.