Litter – pervading the ocean

Top ten marine debris items:

- Cigarettes/ cigarette filters

- Bags (plastic)

- Food wrappers/ containers

- Caps/lids

- Beverage bottles (plastic)

- Cups, plates, forks, knives, spoons (plastic)

- Beverage bottles (glass)

- Beverage cans

- Straws, stirrers (plastic)

- Bags (paper)

Litter: Where does it come from?

Take a stroll along any beach after a storm and you will get an idea of just how much litter is floating around in the world’s oceans: the sand is strewn with plastic bottles, fish boxes, light bulbs, flip-flops, scraps of fishing net and timber. The scene is the same the world over, for the seas are full of garbage. The statistics are alarming: the National Academy of Sciences in the USA estimated in 1997 that around 6.4 million tonnes of litter enter the world’s oceans each year. However, it is difficult to arrive at an accurate estimate of the amount of garbage in the oceans because it is constantly moving, making it almost impossible to quantify. A further complicating factor is that the litter enters the marine environment by many different pathways. By far the majority originates from land-based sources. Some of it is sewage-related debris that is washed down rivers into the sea, or wind-blown waste from refuse dumps located on the coast, but some of it comes from careless beach visitors who leave their litter lying on the sand.

Shipping also contributes to the littering of the oceans: this includes waste from commercial vessels and leisures that is deliberately dumped or accidentally lost overboard and, above all, torn fishing nets. As most of the litter is plastic, which breaks down very slowly in water and may persist for decades or even centuries, the amount of debris in the marine environment is constantly increasing.

Scientific studies have revealed regional variations in the amount of litter in the sea. In many regions, researchers have reported quantities of floating plastic debris in the range of 0 to 10 items of debris per square kilometre. Higher values were reported in the English Channel (10 to 100 items/square kilometre), but in Indonesia’s coastal waters, 4 items of debris in every square metre were reported – many orders of magnitude above the average.

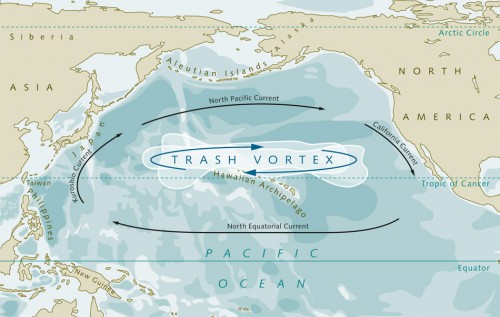

The problem does not only affect the coastal areas, however. Propelled by the wind and ocean currents, the litter – which is highly persistent in the environment – travels very long distances and has become widely dispersed throughout the oceans. It can now even be found on remote beaches and uninhabited islands. In 1997, researchers discovered that the floating debris accumulates in the middle of the oceans – in the North Pacific, for example, where massive quantities of water constantly circulate in a swirling vortex of ocean currents known as gyres, which extend for many hundreds of kilometres and are driven by light winds. The plastic debris ends its journey here. The litter circulates constantly, with new debris being added all the time. Environmental researchers call it the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. The concentration of litter is extremely high, which is particularly worrying if we consider that it is located in the open sea thousands of miles from the coast. Scientists have detected up to 1 million plastic particles per square kilometre here. Much of the debris consists of small fragments of plastic that were fished out of the water using fine-mesh nets. By contrast, studies in the English Channel, and many other surveys carried out elsewhere, are based on the visual method of quantification, which means that scientists simply count the pieces of debris that are visible as they pass by in their research vessels.

The amount of floating oceanic debris is immense. However, it is thought that around 70 per cent of the litter eventually sinks to the sea floor. The worst-affected areas are the coastal waters of densely populated regions or regions with a high level of tourism, such as Europe, the US, the Caribbean and Indonesia. In European waters, up to 100,000 pieces of litter visible to the naked eye were counted per square kilometre on the sea floor. In Indonesia, the figure was even higher – up to 690,000 pieces per square kilometre. Much of the litter is harmless, but some of it is responsible for marine mammal deaths. Seals and otters, for example, which feed on fish, crabs and sea urchins on the sea floor, are frequent casualties.

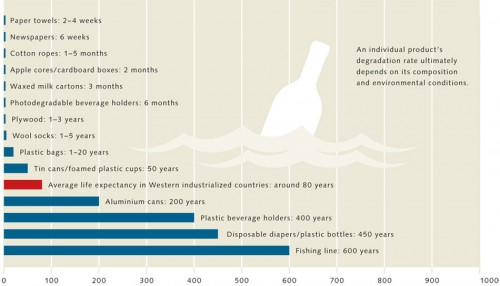

- 4.10 > The amount of litter in the oceans is constantly increasing. Much of it degrades very slowly. Plastic bottles and nylon fishing line are particularly durable. Although many plastics break down into smaller fragments, it will take decades or even centuries (estimated timescales) for them to disappear completely.

Tiny but still a threat – microplastics

For some years now, scientists have increasingly turned their attention to what remains of the plastic debris after prolonged exposure to wave action, saltwater and solar radiation. Over time, plastics break down into very tiny fragments, known as “microplastics”. Microplastics are now being detected in ocean waters, sand and sea-floor sediments all over the world. These tiny particles, just 20 to 50 microns in diameter, are thinner than a human hair. Marine organisms such as mussels filter these particles out of the water. Experimental analyses have shown that the microplastics accumulate not only in the stomachs but also in the tissue and even the body fluids of shellfish. The implications are still unclear, but as many plastics contain toxic substances such as softeners, solvents and other chemicals, there is concern that microplastics could poison marine organisms and, if they enter the food chain, possibly humans as well.

The silent killers – ghost nets

Derelict fishing gear – known as “ghost nets” – poses a particular threat to marine wildlife. These are nets which have torn away and been lost during fishing activities, or old and damaged nets that have been deliberately discarded overboard. The nets can remain adrift in the sea and continue to function for years. They pose a threat to fish, turtles, dolphins and other creatures, which can become trapped in the nets and die. The tangled mass then snags other nets, fishing lines and debris, so that over time, the ghost nets become “rafts”, which can grow to hundreds of metres in diameter. Some of these nets sink to the sea floor, where they can cause considerable environmental damage. Propelled by currents, they can tear up corals and damage other habitats such as sponge reefs.

Impacts on people

For a long time, marine litter was regarded as a purely aesthetic problem. Only coastal resorts attempted to tackle the problem by regularly clearing debris from the beaches. However, as the amount of litter has increased, so too have the problems. It is difficult to put a precise figure on the economic costs of oceanic debris, just as it is difficult to quantify exactly how much litter there is in the sea. In one study, however, British researchers showed that marine litter has very serious implications for humans, particularly for coastal communities. The main impacts include:- risks to human health, including the threat of injury from broken glass, syringes from stranded medical waste, etc., or from exposure to chemicals;

- rising costs of clearing stranded debris from beaches, harbours and stretches of sea, together with the ongoing costs of operating adequate disposal facilities;

- deterrent effect on tourists, especially if sections of coastline are notoriously polluted. This results in loss of revenue from tourism;

- damage to ships, such as dented hulls and broken anchors and propellers from fouling by floating netting or fishing line;

- fishery losses: torn nets, polluted traps and contaminated catches; if nets become choked with debris, the catch may be reduced;

- adverse effects on near-coastal farming: numerous items of plastic waste and other forms of wind-borne marine debris may be strewn across fields and caught on fences; livestock may be poisoned if they ingest scraps of plastic or plastic bags.

Impacts on animals

The presence of such large quantities of debris has a catastrophic effect on marine fauna. Seabirds such as the various species of albatross (Diomedeidae) or the Northern fulmar (Fulmarus glacialis) pick up fragments of plastic from the sea surface, ingest them and then often pass them to their chicks in regurgitated food. It is by no means uncommon for birds to starve to death as their stomachs fill with debris rather than food. Analyses of the stomach contents of seabirds found that 111 out of 312 species have ingested plastic debris. In some cases, up to 80 per cent of a population were found to have ingested debris.

In another study, the stomach contents of 47 harbour porpoises (Phocoena phocoena) from the North Sea were investigated. Nylon thread and plastic material were found in the stomachs of two of these individuals. In other cases, the debris itself can become a death trap. Dolphins, turtles, seals and manatees can become entangled in netting or fishing line. Some of them drown; others suffer physical deformities when plastic netting, fishing line or rubber rings entwine the animal’s limbs or body, inhibiting growth or development.

There is another threat associated with plastic debris as well: almost indestructible and persistent in the environment for many years, plastic items drift for thousands of miles and therefore make ideal “rafts” for many marine species. By “hitch-hiking” on floating debris, alien species can cross entire oceans and cover otherwise impossibly long distances. Plastic debris thus contributes to the spread of invasive species to new habitats, and can even destabilize habitat equilibrium in some cases (Chapter 5).

- 4.11 > In the Great Pacific Garbage Patch between Hawaii and North America, vast quantities of litter are constantly circulating. Many plastic items are transported thousands of kilometres across the sea before they are caught up in the gyre.

4.12 > The Laysan albatross (Phoebastria immutabilis) is also affected by the litter in the Pacific Ocean, as the birds mistake the brightly coloured plastic for food and ingest it. Here, the photographer has laid out stranded items of debris neatly on the beach. These types of objects are typically found among the stomach contents of albatross, and can cause the death of many of the affected birds.

4.12 > The Laysan albatross (Phoebastria immutabilis) is also affected by the litter in the Pacific Ocean, as the birds mistake the brightly coloured plastic for food and ingest it. Here, the photographer has laid out stranded items of debris neatly on the beach. These types of objects are typically found among the stomach contents of albatross, and can cause the death of many of the affected birds.Raising awareness: The first step forward

The fact that marine litter is a problem that must be taken seriously is only gradually being recognized. The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) has therefore launched an intensive publicity campaign in an effort to raise awareness of this critical situation. Its main focus is on working with non-governmental organizations and government agencies to improve the situation at the regional level. This includes promoting the introduction of regulations and practices that in many cases are already the norm in Western Europe, such as waste separation systems, recycling, and bottle deposit-refund schemes. Various litter surveys have shown that much of the debris found in the North Sea, for example, comes from shipping rather than from land-based sources. However, the situation is reversed in many countries of the world, where waste is often dumped into the natural environment without a thought for the consequences and, sooner or later, is washed into the sea. In these cases, shipping plays a less significant role. UNEP is therefore emphasizing the importance of efficient waste management systems.

UNEP also supports high-profile, media-friendly clean-up campaigns such as the annual International Coastal Cleanup (ICC). Every year, volunteers, especially including children and young people, clear litter from beaches and riverbanks. The main aim is to raise young people’s awareness of the problem of global marine litter. In 2009 alone, around 500,000 people from some 100 countries took part in the ICC. Before all the litter is disposed of onshore, each item is recorded. Although the data collection is carried out by laypersons and may therefore contain errors, the International Coastal Cleanup nonetheless provides a very detailed insight every year into the worldwide litter situation.

Indeed, surveying marine litter – i.e., regular monitoring – is an important tool in assessing how the situation is developing. In various regions of the world, professionals have been recording the debris found along the coasts for many years. In the north-east Atlantic region, for example, a standard methodology for monitoring marine litter was agreed to by the Contracting Parties to the Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic (OSPAR Convention), and this has been in effect for around 10 years. Using a common, standardized survey protocol, 100-metre stretches of around 50 regular reference beaches in the north-east Atlantic region are surveyed three to four times a year. It was this monitoring activity that found that the debris in the North Sea mainly comes from shipping.

International agreements lack teeth

For some years, efforts have been made to stem the tide of litter with international agreements. These include the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships, 1973, as modified by the Protocol of 1978 relating thereto (MARPOL 73/78). Since 1988, Annex V to the Convention has specified which types of waste must be collected on board and may not be discharged into the sea. For example, under the MARPOL Convention, disposal of food wastes into the sea is prohibited if the distance from the nearest land is less than 12 nautical miles. Disposal of all plastics into the sea is prohibited. For the EU, on the other hand, Directive 2000/59/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 November 2000 on port reception facilities for ship-generated waste and cargo residues requires ships to dispose of their waste before leaving port and obliges ports to ensure the provision of adequate reception facilities for such waste. Ships must contribute to the costs of the reception facilities through a system of fees.

If a ship has proceeded to sea without having disposed of its waste, the competent authority of the next port of call is informed and a more detailed assessment of factors relating to the ship’s compliance with the Directive may be carried out. Critics point out that both the assessment itself and the communication between ports are inadequate. The fact that there has been no decrease in the amount of debris along the North Sea coast as yet also suggests that the international agreements lack teeth. Annex V of the MARPOL Convention is therefore being revised at present.

In any case, the agreements have no impact on the amount of waste entering the sea from land-based sources. It is hoped that the Marine Strategy Framework Directive (MSFD) – the European Union’s tool to protect the marine environment and achieve good environmental status of the EU’s marine waters by 2020 – will improve the situation. Besides addressing topics such as marine pollution from contaminants and the effects of underwater noise on marine mammals, the MSFD in addition deals with the issue of waste. An initial assessment of the current environmental status of the waters concerned and the environmental impact of human activities is to be completed by 2012, and a programme of measures is to be developed by 2015. The necessary measures must then be taken by the year 2020 at the latest.

Turning the tide against litter: The future

Experts agree that the littering of the seas will only stop if the entry of waste from land-based sources can be controlled. According to UNEP, this means that numerous countries will have to develop effective waste avoidance and management plans. At present, the prospect of this happening seems somewhat bleak, especially given the vast quantities of waste involved. Environmental awareness-raising and education would therefore appear to be a more promising approach. The popularity of the International Coastal Cleanup programme is an encouraging sign that there is growing recognition, around the world, of the need to prevent littering of the seas.

To address the problem of ghost nets, UNEP is calling for stronger controls, which would involve fishermen being monitored and having to log the whereabouts of their nets. Work is also under way to develop acoustic deterrent devices for fishing gear that can, for example, alert dolphins to the presence of nets. The Fishing for Litter scheme being set up in Scotland and Scandinavia is another positive example of action being taken.

Fishermen and port authorities have joined forces so that debris caught in fishing nets can be disposed off correctly onshore. Instead of throwing the litter back into the sea, the fishermen collect the debris on board and bring it back into port. Recycling schemes for old fishing nets are also being developed. In all probability, the global problem of marine litter can only be solved through numerous individual schemes such as these. However, without a concerted effort by the international community as a whole, the problem is likely to continue.