Fishing at its limit

The coming and going of fish

Fish stocks increase and decrease, with or without fishing activity. We have been aware of this natural phenomenon for hundreds of years. In the past it has spelled disaster for many people when fish stocks have suddenly declined. For instance, in 1714 and 1715 the cod inexplicably failed to appear along the barren west coast of Norway. In the poor region of Søndmør the fishermen, to avoid starvation, were forced to sell their most important possession – their boats.

For a long time it was unclear what triggered such fluctuations in fish stocks. Many fishermen and scientists believed that in some years the fish simply migrated to other maritime regions. Finally in 1914 the Norwegian fisheries biologist, Johan Hjort, produced a comprehensive statistical analysis of data he had gathered over numerous research expeditions. One of his most important findings was that variability in the number of fish and offspring is largely dependent on environmental factors – including the salinity and the temperature of the water.

Hjort’s work dates back almost 100 years. Since then, our knowledge about the growth and decline of many fish stocks has increased tremendously. Today we know that many factors impact on the natural development of stocks. We still do not fully understand how everything interacts, however.

The natural factors with the greatest impact include the biotic environment with its species interactions, and also the abiotic environment, particularly the salt and oxygen content, temperature and quality of the water. The latter are also changed by long-term climate fluctuations – a further complicating factor in reaching an understanding of stock development. Of course, the size of fish stocks is not affected only by nature but also by human fishing activity. The condition of an exploited stock can be described by the following three factors:

- STOCK BIOMASS (B) is the total weight of all large and small, juvenile and adult fish in a stock. This figure is estimated with the aid of mathematical models using fisheries’ catch data and scientific samples and is quoted in tonnes. But even these mathematical estimates are riddled with uncertainty. Biomass can also fluctuate greatly from year to year. Of particular significance is the number of adult, sexually mature fish – the spawners – because they are responsible for producing offspring. This section of the stock is known as the “spawning biomass” which is also stated in tonnes. The spawning biomass level is crucial for fisheries scientists because they use it to derive vital benchmarks, known as reference points, used in fishery management. The total biomass of a stock is made up of the spawning biomass and the biomass of the juveniles, which have not yet reached sexual maturity.

- THE FISHING MORTALITY RATE (F) is a somewhat abstract measure of fishery pressure. It can be converted to a relative value which indicates the proportion of the stock biomass which is removed by the fisheries.

- THE PRODUCTIVITY of a stock is calculated by subtracting the number of fish which have died of natural causes from the increase in mass resulting from offspring and natural growth of the fish. This correlation makes it clear that the productivity of a stock is highly dependent on the spawning biomass. It follows that the stock declines when the natural mortality rate and the fishing mortality rate together are greater than the productivity.

- 5.2 > Barren land, poor fishermen: In the Søndmør region of western Norway people’s livelihoods used to depend almost exclusively on fishing, and particularly on the development of fish stocks.

- The offspring production of a fish stock is limited. If the spawning biomass is large, the habitat at some stage reaches its maximum carrying capacity. Even if the spawning biomass then continues to grow, the number of juvenile fish remains at a certain level. At this stage the amount of offspring depends entirely on the environmental conditions. Various factors come into play here: eggs and larvae may be eaten by predators, for example, or starve because insufficient food is available. In addition there can be competition for suitable spawning sites to deposit eggs. The Baltic Sea herring, for example, deposits its adhesive eggs on aquatic plants. When there are too many spawners, they deposit the eggs on top of each other, and those underneath die from a lack of oxygen. As these conditions can fluctuate from year to year, so too does the number of offspring when spawning stocks are high. There can be strong but also very weak years for offspring.

If a stock is exploited too intensively the following can occur. The spawning mass is at some stage so small that few offspring can be produced. In such a case the number of offspring depends directly on the number of spawners. It is no longer capable of reaching its carrying capacity, even when good environmental conditions prevail. The value at which the spawning biomass is so small is called limit biomass (BLIM). The corresponding fishing mortality rate is described as FLIM.

The failure of the precautionary approach

The massive overfishing of many stocks by the industrial fishing industry in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s made the importance of limiting catch volumes abundantly clear. In 1995, the international community adopted a more cautious approach to fishing with the United Nations Straddling Fish Stocks Agreement (UNFSA). In the same year the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) published its Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries. The overriding aim of this precautionary approach (PA) is to prevent a stock from being reduced to such an extent that it can no longer produce sufficient offspring and becomes overexploited. It also stipulates that fisheries should err on the side of caution: the less that is known about a stock and its development the more carefully that stock should be managed, and the less it should be exploited. In principle, therefore, the precautionary approach aims to avert the risk of harm to fish resources. Limits were accordingly set for many commercially exploited fish species, in order to minimize fishing mortality and prevent severe depletion of stock biomass. For example, each year the EU Council of Ministers sets the total allowable catch (TAC) for stocks in the waters of the European Union, thus stipulating how many tonnes of a fish species may be caught in a specific area.

The precautionary approach also takes the dynamics of the stocks into account, because environmental conditions can change the size of a stock. If there is little food available, for instance, the productivity of the stock declines accordingly. The biomass shrinks. If there is plenty of food, the productivity rises and the stock grows. The fishing industry must take these stock fluctuations into account and adjust catch volumes accordingly, not con-tinue to catch the same amount of fish. Such adjustment should be achieved using several benchmarks and limit reference points, terms which are still used for fishing according to the precautionary approach:

- BIOMASS PRECAUTIONARY APPROACH (BPA): It is difficult to predict the status of a fish stock, for several reasons. One is that the current fishery and research data used to calculate fish abundance is unreliable. Another is that all mathematical analysis programs are to a certain extent inexact. There is no 100 per cent certainty. The Limit Biomass (BLIM) is therefore too risky as a reference point. The probability is too great that the biomass does actually fall below this limit in any given year, threatening population growth. In line with the precautionary approach, therefore, it was decided to stipulate a limit reference point which takes such uncertainties into account. This limit is known as the Biomass Precautionary Approach (BPA). It is designed to guarantee that the biomass does not inadvertently fall below the BLIM-threshold. The area between BLIM and BPA is therefore a buffer zone, as it were. Today it is still the most important benchmark used to ascertain the health of many stocks.

- PRECAUTIONARY FISHING MORTALITY RATE (FPA): As the biomass is a fundamentally unreliable and changeable variable which cannot be directly influenced by human activity, it is not practical to stipulate a limit reference point for the fisheries which takes only the biomass as its parameter. Therefore there is an additional limit reference point which is derived from the BPA. This is known as the FPA. This point specifies the maximum fishing mortality rate permissible to stay below the BPA. Scientists use the FPA to calculate the maximum annual catch tonnages for the next season. However, this is only possible when the current status of the stock is known. For this purpose the researchers use the catch data of past years, which provides information on the long-term development of the stock. They then add the catch data from the current season along with the data gathered by research vessels. Finally, they must make assumptions for the current year for which no fisheries data is yet available. From these figures they use mathematical models to estimate the status of a stock for the next season, which forms the basis of their catch recommendations for the fisheries. Adhering to these maximum catch tonnages ensures that fishing remains within the FPA.

Fishing to the limits

In principle the precautionary approach was a good idea. In practice, however, it failed because Fisheries Ministers consistently took the limit reference points to mean the target reference points. Instead of ensuring that limits were not exceeded, they all too often set catch volumes as close as possible to the limit. In hindsight we know that the limits – because of the uncertainties already mentioned – were often violated, meaning that in certain years more fish was caught than the stock could cope with. Moreover, authorities, mainly for political reasons, are even today allowing fishermen to catch more than researchers recommend. The BPA and the FPA were therefore entirely misconstrued by both the fishing industry and the political establishment. The result is common knowledge. In too many cases too many fish were removed, resulting in weakened stocks, particularly in poor years with low numbers of offspring.

MSY – the new route to responsible fishing?

After only a few years, it became clear that the precautionary approach did not work. For this reason, shortly after the turn of the millennium, a different concept was developed which aimed to improve the regulation of fisheries. This traces back to the World Summit on Sustainable Development (WSSD) in Johannesburg in 2002. The summit declared its intention that global fish stocks should be fished to sustainable and responsible limits, the objective being the maximum sustainable yield (MSY). This concept goes further than the precautionary approach which was only designed to protect stocks from overfishing. MSY is designed to manage fisheries efficiently with the aim of preserving stocks and ensuring the highest long-term yields. In other words, the MSY is the largest possible catch volume which can be removed from the sea on a long-term basis without reducing the productivity of the stock. The crucial reference point is the BMSY, or Bio-massMSY. This is the total biomass which allows long-term fish yields in accordance with the MSY concept. It is large enough that neither strong fluctuations in offspring production and individual fish growth, nor years of very weak recruitment will threaten the stock.

- There are already some fisheries around the world which are guided by the MSY concept – off Australia and New Zealand, for example. In most cases the BMSY value is higher than the BPA value used previously, simply because the MSY concept is geared towards the optimal use of a usually larger stock. The BPA, in contrast, was a minimum level. For this reason, the biomass which can deliver the MSY is often larger than the biomass according to the precautionary approach (BPA). Similarly, FMSY is smaller than FPA. Here too, however, there are differences from fish stock to fish stock. The reason why a fishery produces the highest yield with MSY is that there is neither too much nor too little fishing activity. An MSY catch is the happy medium, as it were. If the stock is too small, however, the stock growth is also poor because few offspring can be produced. If the stock is too large it will at some stage reach the carrying capacity of the ecosystem. This happy medium means that the right amount of biomass is produced to replace the amount that dies. With the medium-sized stock aimed for under the MSY concept, there is much less competition for food than in larger stocks with more individuals. The fish find more food, must expend less energy to find it and increase their body weight vigorously. The losses from fishing are offset by the faster growth of the animals. Fishing with MSY also means that more eggs survive and more fish can develop, due in part to the fact that there is cannibalism among predator fish such as the cod: the adult fish partially feed on eggs and larvae. Where there are large numbers of adults, the young are decimated to a much greater extent than occurs with fishing in accordance with MSY. All in all, this means that fishing to MSY levels results in more biomass being available. This is known as excess or surplus production. Surplus production is greatest with MSY.

Unbeatable team: limit and target reference points

The fishing industry and fishing ministries have abused limit and target reference points for far too long. If they had adhered strictly to the scientists’ recommendations, one single point of reference would have been sufficient. A successful fisheries management system based on the MSY concept would consequently need only the BMSY or the FMSY as the limit reference point. But the precautionary approach has shown that this does not work: BPA and FPA were fixed limit reference points, but the fishing industry and policy-makers did not apply them properly – in other words, not in the sense of sustainable fisheries. For this reason the MSY concept today uses a target reference point which the industry can be guided by, and a limit reference point as a safeguard.

This type of approach has already been introduced in Australia and New Zealand. In these countries the FMSY is the limit reference point. In addition, there is a lower target reference point, the FTarget. The fisheries are accordingly required to fish only until this target reference point is achieved as closely as possible. On the other hand, the FMSY in this model, along the lines of the old BPA, is the limit reference point, which should be avoided as far as possible. The essential difference between this and the conventional precautionary approach is that the fisheries no longer align themselves towards a limit reference point but to a lower target reference point (FTarget), which safeguards the FMSY. These values are extremely important for the fisheries because it is from this that clear catch recommendations are derived.

In the greater context of the MSY concept, the stock biomass BMSY is often the desired ideal, so to speak. But here too, because determination is uncertain, the BMSY is in many cases taken as the limit, not the target. In Australia, for example, the biomass target is specified along with a correspondingly higher BTarget. The USA and New Zealand have developed similar models. Although the limit and target reference points in some cases have different names, all the current MSY approaches work with limits and targets and have thus abandoned the precautionary approach which used only the lower biomass limit.

- 5.6 > Fishermen on the deck of the trawler “Messiah” sort cod that they have caught in the Pacific near the Aleutian Islands.

The MSY concept in practice

The MSY concept is of course a theory, an ideal which still needs to be put into practice. For many fish stocks, the problem is that they have been so severely exploited that it is impossible to know the optimal values for biomass, mortality and yield. We do not know the maximum spawning biomass of an unexploited stock, nor can we derive the BMSY with any degree of certainty. For those stocks which were already depleted and recovered after catch limits were set, the best that can be hoped for is the BLIM. One example is the cod in the eastern Baltic Sea, which occurs mainly between Sweden and Poland. The stock was overfished for years, but in recent years it has been able to recover, particularly in Poland, as a result of improved environmental conditions and better controls of catch quotas. For the past two years, however, the stock has hardly grown at all. Apparently the carrying capacity of the habitat has been reached with its current 300,000 to 400,000 tonnes spawning biomass. Although the stock was much larger in the mid-1980s, current food shortages have apparently prevented further growth. This example shows that carrying capacities can change and do in fact fluctuate strongly over the years. For this reason the BMSY cannot be stipulated with any degree of certainty. Furthermore, this biomass analysis does not take into account the age structure of the fish stock. This information is crucial, however, for any assessment of offspring numbers and weight increases in individuals.

- It is also impossible to stipulate BMSY reference levels for many other intensively exploited fish stocks. For these cases we must continue to rely on the old PA values or determine a corresponding fisheries mortality rate FMSY in the coming years. These values can be ascertained even if the BMSY is unknown. The PA values would indeed be meaningful from a purely scientific point of view. They were set on the basis of many years’ experience, catch and recruitment data, and scientific sampling. They have proved to be ineffectual for fisheries management, however.

The original aim of the PA concept was to allow fish stocks to slowly grow as a result of catch limits and then, as with the cod, to observe how a stock develops. To do this, however, policy-makers must set clear targets and limit catches accordingly. In a joint European research project involving more than 10 universities and institutes, researchers are now developing concepts to establish fishing on a sustainable footing in accordance with MSY while fishing continues. Fisheries off Alaska, Australia and New Zealand are already showing that fishing based on the MSY concept is possible. But the starting conditions there were better than in Europe. As industrial fishing only began about 20 years ago, the maximum stock size is known – and this could be used to reliably assess such levels as the BMSY. It is also much easier to manage fisheries in nation states such as Australia and New Zealand than in a union of states such as the EU with its many conflicting opinions.

The aim of the World Summit on Sustainable Development in 2002 was to fish all worldwide fish stocks according to MSY guidelines by the year 2015. This target will not be achieved – mainly because many nations have been too hesitant and have not yet adequately limited fishing. It will therefore still take some years until all European stocks are fished in this way.

One fish species seldom comes alone

Until now fisheries management systems have in most cases examined each species separately. Catch volumes have been stipulated for individual species without considering that these are part of a food web in which the catch of one species also impacts on other species and their development. This applies in equal measure to the initial MSY management approaches. Fisheries should in future pay more attention to these interrelationships between the species. The following two interrelationships can be identified:

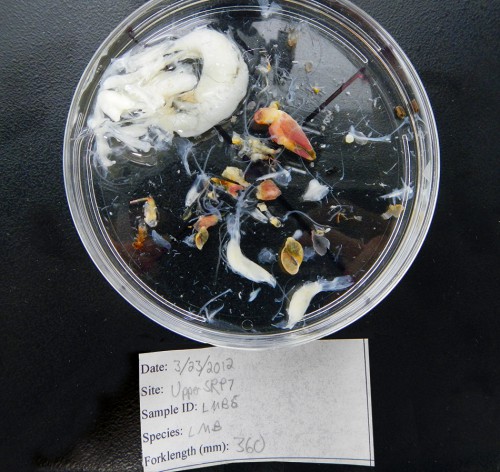

- 5.7 > Stomach content analysis shows what marine fauna feed on – in this case a crustacean, snails and a bullhead, a bony fish.

- MULTI-SPECIES APPROACH: The multi-species approach takes account of the fact that removing one species by fishing also affects other interrelated species within the ecosystem – as predators and prey for example. The multi-species approach takes account of all these interrelationships when calculating catch volumes. For instance, a fish stock should only be exploited to the extent that sufficient food remains for its predators. Depending on how many species occur in a marine area, this multi-species approach can be implemented with different degrees of success. In the Baltic Sea, only 3 protagonists are interrelated as predator and prey – cod, herring and sprat. Scientists believe fisheries management according to the multi-species principle should be possible in the Baltic Sea within the next few years. By contrast, 17 species interact in one complex system in the North Sea. For this area, therefore, it is difficult to develop a multi-species concept. Although scientists have learned a lot in recent years about how species fundamentally interact and prey on each other, little is known about the volumes involved.

Analysing the stomach contents of fish or the faeces of sea birds and marine mammals is one way of determining how much of a given species is eaten. If these analyses are combined with data on speeds of digestion, a rough estimate can be made of how much fish is being consumed. But in most cases the required data is only available for certain years, as individual research projects tend to be time-limited. The data is, therefore, very unreliable. With the aid of mathematical models, however, efforts can be made to reduce these uncertainties and make a better assessment. Various projects are currently attempting to do this. The researchers hope to be capable of making a more reliable evaluation within the next 10 to 15 years.

- CONCEPTS FOR MIXED FISHING: Fish of several different species are often caught in fishing nets at the same time – whether or not they are closely linked within the ecosystem. This is called mixed fishing.

One example is cod and haddock. Both cod and haddock are predators, but they do not prey on each other. Their similar size and habits mean that when one species is caught, the other inevitably ends up in the net too. This makes it difficult to optimize the catch volume for a single species. Cod is more valuable than haddock but occurs in smaller numbers and is classed as overexploited in the North Sea. If we concentrate on catching cod, we can catch very little without placing the stock under further pressure. But at the same time we forgo a large volume of haddock. If, alternatively, we rely on the cheaper, more freely available haddock, cod will also end up in the net as bycatch. Intensive haddock fishing will cause the cod stocks to dwindle. There are many such interdependencies which complicate mixed fishing, especially in the North Sea. Although not all the details are yet known, researchers are hoping to establish an initial pragmatic concept for the North Sea at last, within the next two to three years. This will take the problems of mixed fishing into account and simultaneously optimize the multi-species catch in terms of the MSY.

- 5.8 > Natural beauty against an urban backdrop: for the citizens of Seattle, orcas in the Puget Sound are a common sight.

The ecosystem-based approach – the ultimate discipline

The situation becomes even more complicated if we look at the entire ecosystem – all the fish along with all the other marine dwellers. Currently there is controversy among the experts about whether it is better use of the expensive, time-consuming fishery research expeditions to find out more about the development of individual fish species – or whether all species in the ecosystem should be recorded as a whole in order to increase our understanding of the food web. Although our knowledge of these interrelationships has increased enormously, particularly over the past 20 years, we are still a long way from implementing an ecosystem-based fisheries management regime.

US researchers have developed a concept for ecosystem-based fisheries management in the Puget Sound off Seattle on the west coast of the USA, and are showing how this could perhaps function. Although not yet introduced by the US authorities, this concept is considered by other experts to be viable and could serve as a model for other parts of the world. The researchers analyse the extent to which a certain species may be exploited without causing any damage to the environment. They also take into account other human impacts on marine life such as construction work, shipping and tourism.