Issues with fisheries

Fish consumption

The term “fish consumption”, as used by the FAO, encompasses all fish species as well as molluscs, crustaceans and other aquatic organisms that are farmed or caught for human consumption.A growing appetite for fish

Not only do people enjoy eating fish, clams, crustaceans and other seafood – per capita consumption is rising steadily. In recent decades the global demand for aquatic foods has grown so rapidly that today twice as much fishery produce is produced for human consumption as 40 years ago. The global population grew over the same period from 5.6 to 7.6 billion people; this can only explain a part of market expansion. The main reason appears to be a mounting appetite for fish. While it has been calculated that the average citizen of the world ate around 13.4 kilograms of fish each year during the period from 1986 to 1995, the most recent fisheries report of the FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations), from the year 2018, gives a per capita consumption of 20.5 kilograms per year. This report includes fishery products from the ocean as well as those from lakes, rivers and ponds.

Worldwide, fish and seafood account for 17 per cent of the total amount of animal protein consumed by humans. A detailed study of who eats fishery products indicates that more than 3.3 billion people obtain at least one-fifth of their animal protein requirements through aquatic foods. In countries like Bangladesh, Cambodia, Gambia and Indonesia, this share approaches as much as 50 per cent, which means that fish products play a paramount role in the food supply of the populations there. Germany ranks near the middle of this range. While every citizen of Indonesia eats more than ten grams of fish protein each day, Germans, according to the FAO statistics, average four to six grams per day. The annual per capita consumption in Germany is between ten and 20 kilograms of fish (live weight).

- 3.1 > Fish and seafood are caught and consumed around the world, but in very different quantities. In South East Asia, Western Europe, Scandinavia and Greenland people consume considerably more fish than in northern Africa, in eastern South America, or in the Near East.

- The increasing worldwide fish consumption can be attributed to a number of factors. For one, more fish and seafood are being produced. For another, demographic changes and improvements in freezing and delivery chains have contributed to the more frequent appearance of fish on the plates of people in industrial countries, but also in developing countries where urbanization is advancing. Statistics indicate that in areas where people are moving from the country to the cities, and are beginning to earn higher incomes for extended periods of time, they also purchase more fish and seafood or order more of these foods at street stands and restaurants. Moreover, in many places fish is cheaper than meat and is considered to be an especially healthy option because of its vitamins, essential polyunsaturated fatty acids (Omega-3 fatty acids) and low cholesterol content. According to the FAO, developing countries imported around 49 per cent of the globally traded fishery produce in 2018. This means that the import share of these countries has more than doubled over the past four decades.

- 3.2 > Fish are an important source of protein. They also contain many vitamins and nutrients, as well as polyunsaturated Omega-3 fatty acids, which are the crucial building blocks of cell membranes. A less well-known fact is that heavy metals, dioxins, marine biotoxins like ciguatoxin, and antibiotics may also accumulate in fish meat.

- The increasing consumption rates are made possible by more intense fishing activity in open waters, and by the rising production of food fish and other organisms by aquaculture methods. While global fish and seafood production was around 140 million tonnes in 2006 according to the FAO, by the year 2018 it had risen to around 179 million tonnes. Around 46 per cent of that (82 million tonnes) came from aquaculture and the remaining 96.4 million tonnes were caught wild by fishermen and -women.

Marine fisheries still make up the largest proportion of wild catches today. In 2018 they accounted for around 84.4 million tonnes. This is equal to a share of 88 per cent and is only two million tonnes less than the previous peak value from the year 1996. The seven most important marine fishing nations, in order, are China, Peru, Indonesia, Russia, the USA, India and Vietnam. Together they are responsible for more than half of all the catches in the oceans.

- 3.3 > The amounts of fish caught, as well as the fish and seafood produced in aquaculture, have been rising worldwide for decades.

3.4 > Fisheries and aquaculture provide a livelihood for more than ten per cent of the world’s population. Most of the small-scale fishers live in Asia. This woman is selling her catch at a market in Vietnam.

3.4 > Fisheries and aquaculture provide a livelihood for more than ten per cent of the world’s population. Most of the small-scale fishers live in Asia. This woman is selling her catch at a market in Vietnam.

- After constant growth in the numbers of fish caught each year, which lasted into the 1990s, the production levels for marine fisheries levelled off, and have now remained relatively stable since 2005. The official total amount over the past 15 years has generally been in the range of 78 to 81 million tonnes annually. A notable peak in 2018 can primarily be attributed to the activities of Chilean and Peruvian anchovy fishers. In that year they caught significantly more Peruvian anchoveta (Engraulis ringens) with their nets than in the preceding three years.

The FAO now records fishery data for more than 1700 marine fish species. But it is difficult to say to what extent their figures truly reflect the actual catches. In its report, the FAO itself points out that it mainly works with official catch data submitted by the individual countries. If there is important data missing from these catch reports or if nations refuse to cooperate with the FAO, as is the case with Brazil, the organization attempts to fill the gaps by estimating the amount of the missing catches. To do this, it draws on other official sources, such as statistics from the Regional Fishery Bodies (RFBs) and from regional fisheries management organizations (RFMOs).

International cooperative research initiatives like the Sea Around Us project try to combine official catch data from the FAO with estimates of bycatch, as well as with illegal or unreported landings. As might be expected, there is a great deal of uncertainty in their scope. At any rate, their method results in higher estimates of the totals of fish caught worldwide. For example, in 2016 according to Sea Around Us, some 104 million tonnes of ocean fish and other marine animals were caught. For the same year, however, the FAO reported catches of only 78.3 million tonnes of marine fish species. The difference of 25.7 million tonnes reflects illegal or unreported catches. 8.1 million tonnes of these, about 7.8 per cent of the total catch, were thrown overboard as bycatch. According to these figures, approximately every fourth fish that is caught is not accounted for in the FAO statistics.

- 3.5 > For its statistics, the Sea Around Us research project combines officially reported catches with estimates of illegal fishing excursions and also includes bycatch that is discarded directly into the sea again. Their calculated total amount of fish caught is therefore significantly higher than that reported by the FAO.

- Critics also argue that the FAO’s figures on the trends in wild catches and aquaculture production fail to address two important aspects. First are the amounts of wild sardines, herring, sprats and other schooling fish that are caught and processed into animal feed such as fishmeal and fish oil, and are thus not used for direct human consumption. These account for an estimated 25 per cent of all marine catches. The second is that in reporting the aquaculture portion, the weights they use for shellfish include the shells. In farmed animals like oysters, however, the shells make up as much as 80 per cent of the total weight but they are not ultimately eaten. For this reason, according to the critics, the total production by the aquaculture industry is not equivalent to the amount of food produced. That amount should be accordingly smaller.

Mostly anchovies and pollock in the nets

If the FAO total catch figures from 2017 to 2018 are broken down into individual fish species, the Peruvian anchoveta (Engraulis ringens) clearly stands out over the rest. More than seven million tonnes of this schooling fish, which can be up to 20 centimetres in length, were caught off the west coast of South America in 2018. It is thus unquestionably at the top of the list of the world’s most heavily fished species. Pacific pollock (Theragra chalcogramma), which is known as Alaska pollock on the German market, comes in second place with a total of 3.4 million tonnes. Third place, at 3.2 million tonnes, goes to the skipjack tuna (Katsuwonus pelamis), the most heavily fished of all tuna species. It lives mostly in the tropical and subtropical seas, but is also occasionally caught in the North Sea.

- 3.6 > Most fish are caught in the temperate latitudes. But fishing in the tropics is growing steadily.

- Tuna and similar species are being more intensively fished every year. This trend continued in 2018, reaching a new peak of 7.9 million total tonnes. The rise can be attributed to greater numbers of fishing excursions in the western and central Pacific. While around 2.6 million tonnes of the skipjack, yellowfin (Thunnus albacares) and other tuna species were caught annually in the mid-2000s, this value is now up to 3.5 million tonnes. The amounts of cephalopods caught reached a similar level. The most abundantly fished species of these were the Humboldt squid (Dosidicus gigas), the Argentine shortfin squid (Illex argentinus) and the Japanese flying squid (Todarodes pacificus).

In recent years, fishing has increased significantly in the tropical regions of the Indian and Pacific Oceans. But the largest catches are still being made in the middle latitudes with their temperate climate. In 2018, around 37.7 million tonnes of marine species were caught here.

- 3.7 > The Japanese flying squid Todarodes pacificus lives in the northern Pacific and is one of the most heavily fished of all cephalopods. Catch numbers have been declining in recent years, perhaps because population numbers have plunged by more than 70 per cent.

Much too heavily fished

When catch numbers increase steadily or are sustained at high levels, the question of the damage that fishing is inflicting on the ocean’s biological communities will eventually have to be addressed. A definitive answer to this question is not possible, however, because we do not know enough about the status of most fish stocks. This is due to a paucity of scientific data. It is not known how large these stocks were originally or how much they have been depleted due to fishing, which is why there are no management or protection concepts for these marine fish species and stocks. Nevertheless, unmonitored species are being fished so extensively that the catches make up about half of all the global marine fish landings.

The other half, however, are from scientifically monitored fish populations. These are generally species that constitute large populations, are fished on an industrial scale, and are native to waters where industrialized nations have primary oversight. Scientific evaluation of the stocks and monitoring of fisheries requires money as well as effective fishery authorities, which is why there is a notable lack of reliable information on the state of the stocks and the scale of fisheries in developing countries.

But even when these data are available, it can still be difficult to determine the productivity of a fish population and the maximum numbers of fish that can be taken under the existing environmental conditions without causing long-term damage to the stocks. There is a very wide range of opinions, even among fishery biologists. A fish stock is generally considered to be healthy when it contains a sufficient number of animals for a maximum sustainable yield (MSY) of fish to be removed without causing a long-term impact to the size of the population. Under this concept, enough individuals always remain in the water for their offspring to replace the stocks sufficiently for the MSY of fish to be taken again the following season. The FAO refers to this situation as a stock that is fished at the maximum sustainable level. However, this wording commonly leads to misunderstandings. People often equate the size of sustainably fished stocks with the size of natural, unfished populations. Actually, the former is usually 30 to 50 per cent smaller than the latter. Only populations that are not fished at all can reach their natural stock size.

- 3.8 > A clear downward trend: According to the FAO, 34.2 per cent of all scientifically monitored fish stocks were overfished by the year 2017. 6.2 per cent were underfished and 59.6 per cent were fished at the maximum possible sustainable levels.

- A stock is considered to be overfished if the remaining population is too small to completely recover and produce consistently high fishing yields over the long term. This condition is becoming more and more common around the world, as the number of stocks known to be exploited beyond their resilience limits has been increasing for decades. There are thus ever fewer fish in the sea. According to FAO figures, one in ten scientifically assessed stocks (ten per cent) was considered to be overfished in 1974, but by 2017 that number had increased to 3.4 in ten (34.2 per cent). In other words, the proportion has more than tripled in four decades. In 2017, only 6.2 per cent of all known fish stocks were considered to be lightly fished or underfished. The remaining 59.6 per cent, according to the FAO, were fished at a sustainable level. That means that the number of fish removed was not more than the number that could be naturally replenished.

Even more grave are the findings of a recent study by Canadian and German fishery biologists of the population development trends of 1300 marine organisms over the past 60 years, including invertebrates, using the combined catch data from Sea Around Us. By their assessment, 82 per cent of the populations surveyed are now below the levels necessary to produce maximum sustainable yields. This means that more animals are being removed than can be replaced. In the long run, therefore, according to the researchers the fishers will bring home smaller and smaller catches, even when they fish more intensively and for longer periods of time.

- 3.9 > The FAO comparison shows that the Mediterranean and Black Seas are among the most intensively fished marine regions in the world.

- Marine conservationists and many scientists are therefore calling for rejection of the popular singlespecies management strategy, moving instead towards maximizing sustainable fisheries yields. The large number of overfished stocks shows that the old approach is no longer sustainable, and that it ignores the role of fish in the food webs of the seas. By fishing to the very limits of sustainability, critics argue, humans also leave no buffer or margin for species to react to changing environmental conditions. For example, if the reproduction rate of a species declines because the waters in its spawning areas become warmer due to climate change, the catch limits for maximum sustainable yield can change very rapidly. Intelligent fisheries management, on the other hand, as practised to some extent in the European Union and particularly in the USA, aims at somewhat lower yields. This reduces the risk of unintentional overfishing and makes the populations less susceptible to environmental changes.

In the European Union, for example, fisheries managers do not look only at the stock size of the species. Instead, they work in a more process-oriented manner and pose the question of how high the fishing mortality of a stock can be and still achieve and maintain its MSY size over the long term (FMSY). According to scientific opinion, therefore, the recommended catch quotas, as a rule, should be smaller than the theoretical maximum. From this point of view, the only thing that would conserve resources more effectively would be to stop fishing completely.

The reality, however, is that in many places a fish stock being designated as overfished does not stop fishers from continuing to target that species. In the Mediterranean and Black Seas, for example, the FAO now classifies 62.5 per cent of the actively fished stocks as overfished. Ceaseless fishing pressure throughout recent decades has led to the eradication of at least 17 popular fish species in the Turkish sectors of the two Seas, including the Atlantic bluefin tuna (Thunnus thynnus), the swordfish (Xiphias gladius) and the Atlantic mackerel (Scomber scombrus). Their disappearance has set off chain reactions in the affected ecosystems. For example, mackerel predators like the porbeagle (Lamna nasus) have not been sighted in the Turkish coastal waters in decades. The same is true for white sharks (Carcharadon carcharias), which, until the 1980s, had been known to follow migrating schools of tuna as far as to the Sea of Marmara. Today these great predators are considered to be extinct in this part of the Mediterranean.

Conflict of interest at the cost of the sea

Overfishing of the seas is not a new phenomenon. Fishermen had recorded sharply declining catch numbers as early as the 1970s, for example, when the herring stocks in the northeast Atlantic collapsed in response to very heavy fishing pressure. Also at that time, the stocks of Peruvian anchoveta shrunk dramatically and the cod fishery in the waters of Newfoundland collapsed. Concerns about domestic fish stocks prompted some coastal states to establish an Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) 200 nautical miles wide, where fishing by foreigners was prohibited from that time on. This approach was subsequently adopted in the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which entered into force in 1994.

- 3.10 > By the year 2020, so few herring and cod remained in the western Baltic Sea that these two fish species could no longer produce enough eggs for their entire spawning area. Climate change, aided by the comb jellyfish, finished them off, and the search for juvenile fish by researchers and fishers was in vain (l.: herring larva, r.: cod larva).

- With the Exclusive Economic Zone at their doorsteps, the industrial nations, at least, began to keep track of catch statistics and to scientifically monitor the condition of stocks. In the mid-1990s, increasing numbers of research papers and media articles began to appear reporting that the catches of many key species had collapsed dramatically due to overfishing. And in June 2003 a globally acknowledged report by the Pew Oceans Commission on the health of the oceans described overfishing as a serious threat for the first time.

Alarmed by the prospect of collapsing stocks, many countries, particularly the industrialized nations, began to regulate fishing in their Exclusive Economic Zones. They were successful in some areas. But countries of the European Union, among others, still lack strong political will to give top priority to marine conservation and to follow scientific recommendations on fishing restrictions. The main reason is that they have not been able to satisfactorily answer the question of how people whose livelihood has depended on the catching of wild fish will earn a living in the future.

Fish and fishery products are now among the most abundantly traded foodstuffs in the world. In 2018, the total first-sale value of all fishery products produced by capture fisheries and aquaculture came to USD 401 billion. At that time, fisheries and aquaculture together represented the livelihood of around ten per cent of the world’s population. In the year 2018, according to the figures of the FAO, around 39 million people worldwide worked directly in the fishing industry (including inland fisheries), while 20.5 million people were employed globally in aquaculture farming. Compared to the reporting year of 2015, both sectors had shown moderate growth.

3.11 > An Indonesian aquafarmer wades through his fully stocked shrimp-breeding pond. This Asian country, after China, is the second-largest aquaculture producer in the world, with annual growth rates of up to 12.9 per cent.

3.11 > An Indonesian aquafarmer wades through his fully stocked shrimp-breeding pond. This Asian country, after China, is the second-largest aquaculture producer in the world, with annual growth rates of up to 12.9 per cent.- 85 per cent of all fishers and aquaculture farmers live and work in Asia. By no means does the typical fisherman or -woman work on a large trawler. FAO statistics indicate that around nine out of ten of the workers are from developing countries, where they earn their livings in small-scale fishing or aquaculture facilities. In Europe, as well as in North and South America, on the other hand, the number of people working in the fisheries industry has been declining in recent years. In 2015 there were 338,000 Europeans working in fisheries, but just three years later this figure had fallen to only 272,000. By comparison, around 30.8 million people in Asia earned their livings in fisheries in 2018.

To date, more than 95 per cent of all fish landings take place within the Exclusive Economic Zones. This means that fisheries management is primarily the responsibility of the individual nations. These use various instruments and strategies to manage their stocks.

Experience over the past three decades has shown that overfishing can be reduced and stocks be conserved through systematic regulation. Nevertheless, not every measure tried was effective in achieving the desired ecological improvements. Some of the regulations left too many options for circumvention by the fishers, while others worked for species with high reproduction rates but failed for species with fewer offspring. Still other guidelines can be implemented on a local scale – for example, in remote, small fishing communities – but are not suitable for industrial-scale fisheries.

The secret plundering of the seas

Leaving unwanted and discarded bycatch out of the calculation, about every fifth or sixth ocean fish that is bought or prepared around the world is caught illegally. This falls under the official designation of illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing.

“Illegal fishing” is considered to be all fishing activities that violate applicable national and international regulations or the rules of the responsible regional fisheries management organizations. The category of “unreported fishing” includes fishing excursions whose catches are not reported to any official authorities, trips on which false information about species fished, fishing area, or amount of bycatch is provided, or those on which other required information is withheld, for example, relating to the transfer of catches to reefer ships. Strictly speaking, subsistence fishing (fishing for personal consumption) as well as catches by small-scale fishers are also part of the unreported fisheries in many countries. But in these cases, presumably, no one would accuse the fishers involved of criminal activity.

“Unregulated fishing” refers to fishing activities for which there are still no national or international control bodies, but which nevertheless violate international laws or globally applicable principles and conventions for the conservation of biodiversity. This includes, for example, fishing by ships that are not registered anywhere and are therefore stateless, or fishing in particular RFMO waters although the flag state of the vessel is not a member of that RFMO.

- 3.12 > The endangered totoaba from the eastern Pacific Ocean is mainly caught by Chinese deep-sea fishers. It is targeted because on Asia‘s markets a single swim bladder of this coastal fish will bring a price of USD 1400 to 4000 for its alleged healing properties.

- The temptation to carry out IUU fishing is great. One reason for this is that high-value food fish such as tuna bring a high price. Another is that fish and seafood are traded on a global market. According to the FAO, around 38 per cent of all fishery products in 2018 (wild-caught and aquaculture) were for export. The value of these goods was USD 164.1 billion. Experts estimated the sale value of illegal catches at USD 10 to 23 billion. But the ecological, economic and societal damages that are incurred due to illegal fishery are thought to be much higher.

In many cases, experts are now referring to this problem in terms of transnational organized crime, the scope of which not only threatens marine ecosystems in a dramatic way but is also creating a security problem. Large-scale illegal fishing operations by foreign fleets in the coastal waters of African countries, for example, are depleting or destroying the local fish stocks and endangering the food security of the coastal populations. Livelihoods are being stolen from the small fishers, and this can encourage criminal activities, including piracy. Added to this, the countries are losing millions in tax income. Furthermore, illegal fishing operations are undermining local, regional and international conservation efforts. If the extent of IUU fishing in a marine region is not known, and the lack of information results in incorrect estimates of its stock and catch numbers, there is very little chance of success in protecting the stocks.

Furthermore, illegal fishing is often connected to human rights abuses and slavery, especially in South East Asia. According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), numerous victims have reported extortion, psychological and sexual abuse, fatal accidents caused by the lack of safety measures on board fishing vessels, and extremely hard and dangerous work for starvation wages.

- Experts recommend a range of measures to stop systemic IUU fishery. These are based on the concept that large-scale illegal fishery should no longer be seen as a management problem, but as a type of organized crime, and should be prosecuted as such. Everyone involved must be informed of the fact that other criminal activities are often linked to illegal fishing, including corruption, falsification of documents and human trafficking. To stop the plundering of the oceans, coastal states must strengthen and rigorously enforce their fishery laws. It is the duty of the international community to not only support the nations concerned in monitoring their coastal waters, but also to establish clear rules, functions and responsibilities in the fight against illegal fishing at the international level.

At the same time, mechanisms must be implemented that help to make information about ships, their owners, routes and fishery licenses more easily available. The lack of information about active participants and other responsible parties is still one of the greatest obstacles in the fight against illegal fishing. In addition, regional networks and partnerships between governments, agencies and environmental organizations need to be expanded, and cooperation among the states strengthened in the area of maritime security. It is also essential to expose and prosecute the financial transactions and money laundering processes associated with illegal fishing.

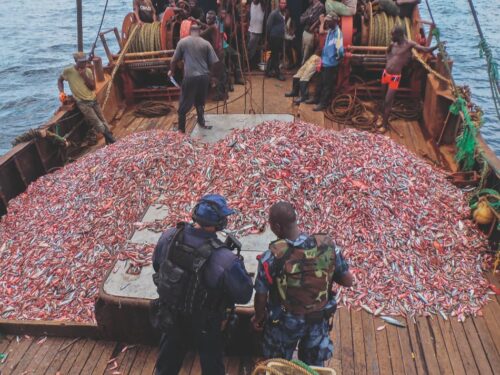

- 3.13 > A team of US American and Ghanaian coastguard officers inspect a ship in the Gulf of Guinea that is suspected of illegal fishing. Seafood is the most important source of animal protein for the people of Ghana. But the coastal waters of this African country have been overfished for decades.

- There are two relatively new and important tools being used in the struggle against large-scale fishery crimes. One is modern satellite and positioning technology, and the other is the international Agreement on Port State Measures (PSMA) to prevent, deter and eliminate illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing. This pact entered into force in 2016 and had been ratified by 66 states by February 2020. It empowers coastal states to block entry of ships under foreign flags to their harbours when there is reason to believe that they are involved in illegal fishing activities and have such catches on board.

It is important to note that illegally caught fish generally enter the market through one of two pathways. In one case, the trawlers transfer their catches onto a freezer or factory ship while still at sea, where the fish are then immediately processed and may be mixed with products from legal catches. It is then practically impossible for inspectors, intermediaries or customers to trace the provenance of the individual fish filets, which is why the transfer of catches on the open sea is prohibited by some regional fisheries management organizations. Nevertheless, this practice is carried out in many places, and is the reason why transshipment is seen as one of the biggest loopholes for illegal fisheries. The second way to get them into the market is to transfer large amounts of the illegally caught fish into deep-freeze containers, then reload these onto a container ship in a nearby harbour and send them out into the world from there. The advantage here is that freezer containers are less frequently inspected in the harbours compared to other transported goods. In addition, less specific information about the container’s contents is required. In a 2016 report on illegal fishing in West African waters, investigators concluded that 84 per cent of all official and unofficial catches in West African waters were transferred to freezer containers and left the region through a handful of ports heading to other countries such as Spain.

The PSMA regulates, among other things, the information and documents a harbour authority should demand when a (reefer) vessel requests permission to enter the port. It also prescribes on-board inspections and a thorough exchange of information between all responsible parties. In addition to the national authorities of the coastal state concerned, these include the government of the state under whose flag the vessel in question is sailing, the responsible regional fisheries management organizations and international institutions such as the FAO. Experts believe that if it is correctly implemented the PSMA could help to bring an end to systematic, large-scale illegal fishery, because it would prevent the landing and further transport of illegal catches.

- A new web portal showing the locations of large reefer and factory ships (Carrier Vessel Portal), which went online in the summer of 2020, will also bring greater transparency. On the portal, which is operated by the environmental group Global Fishing Watch and combines positioning and satellite data, registered users can, for example, analyse the routes of industry ships, or find out which ports they regularly enter. The vessel names can then be checked against the positive and negative lists that are now published by several regional fisheries authorities.

It is the view of the FAO that the flag states need to assume a greater role in the efforts against illegal fishing. With its FAO Voluntary Guidelines for Flag State Performance, it calls on all nations to respect international law, to ensure observance of national and international fishery regulations, to fulfil their inspection obligations, to prosecute illegal activities by their own fishing fleets and to share relevant information and cooperate more closely with national and international institutions. In this way, fishers who have been proven guilty of criminal activities could be prevented, for example, from cancelling their ship’s prior registration in order to register with a less restrictive country. This technique of avoiding the law is known as “flag hopping”. The FAO has no means of forcing flag states to honour the guidelines, however, because their implementation is still voluntary. The same is true for FAO guidelines on the documentation of fish catches, which are meant to allow the states, fishery organizations and other stakeholders to establish transparent supply chains, making it possible at any time to verify whether fish products of any kind are from legal catches.

Pursuing criminals with satellites and positioning data

Proving the illegal activities of fishers has largely been unsuccessful so far due to the vastness of the oceans and the shortage of funds for personnel and equipment in many places. These surveillance gaps can now be closed with the help of modern satellite and positioning technology, as a report published in June 2020 by two environmental organizations specializing in fishery issues shows. They analysed radio and satellite data from the Arabian Sea (northwest part of the Indian Ocean) and discovered that during the fishing season of 2019/2020 alone more than 110 Iranian fishing vessels entered and illegally cast their nets in the territorial waters of Somalia and Yemen. Fishers from India, Pakistan and Sri Lanka did the same, although in much smaller numbers.

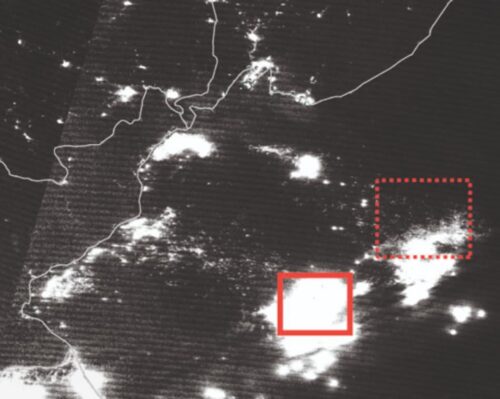

- 3.14 > The green lines on this map show the routes of 175 Iranian ships that fished in the Arabian Sea between 1 January 2019 and 14 April 2020. More than 110 of them illegally entered the territorial waters of Somalia and Yemen.

- Evidence of illegal fishing in Somalian waters has been available for some time. The true magnitude of the crimes, however, only became known after scientists began to deliberately search for clues. Their work was facilitated by the fact that more and more ships around the world are being fitted with an Automatic Identification System (AIS). The system was first developed as an aid to prevent ship collisions and is now required equipment on all larger ships (gross tonnage of 300 or more). Position coordinates are transmitted every few seconds along with the course and speed, and every three minutes the basic ship information is sent out, so that other nearby ships have access to up-to-date information and can adjust their course as necessary.

Although the data transfer system was originally designed only for direct contact between ships, today the AIS signals are also received by radio towers and satellites and recorded by data centres. In this way, observers of fishery activities around the world can trace the routes of large fishing vessels (over 24 metres long) in real time, and are thus much better able to estimate the total number of ships in operation. Fishing vessels less than 24 metres long generally do not have an AIS on board. According to the FAO, around 60,000 fishing vessels were located and identified in 2017 using AIS data. At the time only 20,000 of those were listed in publicly available registers.

- 3.15 > Bright lighting visible on satellite imagery taken on 25 September 2019 reveals the Chinese squid-fishing fleet off the coast of North Korea. Meanwhile, North Korean fishers are moving into Russian waters. Because they use fewer luring lights than the Chinese, their ships appear less brightly on the images.

- However, monitoring of the fishing fleets using AIS can only work if the systems remain switched on. For example, in recent years it has been shown repeatedly that Chinese fishers have deliberately turned off the positioning systems of their ships in order to conceal their locations. In 2019, this ploy was used by as many as 800 ships to fish illegally off the coast of North Korea for Japanese flying squid (Todarodes pacificus). Global Fishing Watch only managed to detect the fleet because the bright lights of the ships were visible on satellite images. For squid fishing, the ships hang bars with as many as 700 light bulbs over the water to attract the animals to the sea surface. Since 2003, the stocks of this very popular squid have declined by 70 per cent. Now, knowing the intensity with which China has been pursuing this species year in and year out, the reason for the plummeting stocks has been revealed.

Because of these kinds of offences, an absence of transparency, neglect of its obligations as a flag state, and a number of other failures in the fight against illegal fishery, China is considered to be the world’s worst-performing coastal state, followed by Taiwan, Cambodia, Russia and Vietnam. The best records are achieved by Belgium, Latvia, Estonia, Finland and Poland, all of which are European countries.

A look at the total ecosystem

Despite the negative headlines regularly received by China’s fishing fleet, there is hopeful news on other fronts. For example, the FAO is seeing increasing evidence that where fish stocks are carefully monitored, and catch quotas adhered to, previously overfished populations are often capable of recovering. The Atlantic menhaden (Brevoortia tyrannus) of the herring family, also known as bunker, is one of these encouraging examples.

This schooling fish is known to be a key link in the food web along the Atlantic coast of North America. It is a source of food for all of the large predators. Humpback whales, dolphins and seabirds prey on it, as do some highly valued and desirable food fish such as tuna, striped bass (Morone saxatilis) and bluefish (Pomatomus saltatrix). In addition, menhaden are fished on a large scale to be processed as fishmeal that is used as feed in agriculture or aquaculture. The species is also used as a bait fish and in the production of fish oil.

- No other fish has been caught in greater numbers along the east coast of North America in a single year than this species. Until ten years ago this fishery was carried out almost completely unrestrained, which resulted in drastically reduced stocks. In order to stop the plunging trend, fisheries authorities introduced catch quotas in 2012, strictly enforced their compliance, and had the stocks monitored through an ambitious scientific support programme. Since then, the schools of herring have been growing again, which has led to a noticeable improvement in the ecosystem along the east coast of the USA that also benefits the people there. Humpback whales now regularly follow the schools of herring into New York Harbor, which is a great boost to the tourism industry because both locals and visitors want to see these marine mammals close up. And in the US state of Maine there is again sufficient bait fish for the lobster fishery.

In August 2020, the fishery authorities took a further step. Under pressure from scientists, ornithologists, fishers and environmentalists, they unanimously decided that fishing quotas should no longer consider only the size that herring stocks need to be in order to renew themselves (single-species management), but instead should be based on a multi-species management approach that also takes into account the needs of marine predators, especially the striped bass. Under the new policy, fishers are limited to catching a volume of herring that will leave the striped bass enough food to reproduce at a level for their stocks to recover. The predator fish in this case serves as the ecological reference point.

- 3.16 > Based on 40 indicators, fisheries experts have compiled an index for all of the world’s 152 coastal states that indicates the extent to which each country experiences and combats illegal and unreported fishing. The higher the index and the longer the individual fish bones are depicted in the figure, the worse the country’s performance is in its response to illegal fishing.

Deep-sea fishery

“Deep-sea fishery” generally refers to fishery on the high seas where water depths are from 200 to 2000 metres. The most common method of fishing here is with trawl nets.- The basic idea behind this concept is to take into account the health, productivity and resilience of the entire ecosystem when determining catch quotas, including the needs of all the marine organisms that depend on a particular fish species. Scientists refer to this principle as the ecosystem approach. Unlike fisheries management concepts of the past, this approach does not focus on a single species, sector or problem. Instead, officials are encouraged to consider the many dependencies and interactions within marine communities, and to examine the ways in which human intervention is altering them. Fisheries management using the ecosystem approach is characterized by:

- a focus on conservation of the ecosystem, its structures, functions and processes;

- consideration of the relationships between desirable target species such as herring and those species that are of less or very little interest;

- recognition that the health of the seas also depends on processes on the land and in the air, and that the land, ocean and atmosphere represent a closely knit system;

- incorporation into its design of the ecological as well as social, institutional and economic perspectives, and the extent to which these influence each other;

- appreciation not only of the consequences of fisheries for the respective ecosystems, but also the consequences of all human activities, thus including climate change.

- The FAO had developed recommendations for implementing this approach as early as 2003. Since then, most of the industrial countries involved in fishing as well as the majority of regional fisheries management organizations have adopted it and adapted their regional and national regulations accordingly.

But, in the opinion of many fisheries experts, there is still a lot of room for improvement with regard to its implementation. There is a need not only for political will, but also for more scientific data on all aspects of fisheries. The USA is leading the way so far, and is investing a great deal of time and money in the monitoring of their fish stocks. Experience has also proven that successful fisheries management brings all of the relevant and affected interest groups into the decision-making process. The local coastal communities must have a say, as well as business representatives, scientists, government leaders, environmentalists and representatives of other sectors that are influenced by fisheries. The success that can be achieved through this kind of cooperation at all levels is clearly illustrated by the recovery of the large schools of the Atlantic menhaden.

- 3.17 > Fishers in the Vietnamese province of Phú Yên cast a net around a school of anchovies. This coastal region is known for its anchovy fishery. The countless millions of the schooling fish that they catch are mostly processed into fish sauce.

More protection for the high seas

Effective protection measures by individual nations are largely limited to the coastal waters within their own Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs). International waters, officially referred to as the high seas, begin at the outer boundaries of the EEZs. Basically, anyone is permitted to fish in this area. In recent decades a relatively small number of states have increasingly begun to take advantage of this right. This may be because of overfishing in their own coastal waters, because the demand and thus the selling price for fish have gone up, a result of technical innovations that have made high-seas fishing more practicable, or due to government subsidies of these fishing activities that have made them more profitable. The ten leading high-seas fishing nations are China, Taiwan, Japan, Indonesia, Spain, South Korea, the USA, Russia, Portugal and Vanuatu.

However, only since the introduction of automatic ship information and monitoring systems has it been possible to identify the marine areas in which the fleets are casting their nets. In a global analysis of high-seas fisheries in 2016, scientists were able to track the routes of at least 3620 fishing vessels, 35 tankers and 154 reefer vessels. Far more than three-quarters of them came from China, Taiwan, Japan, Spain and South Korea. The fishing operations covered an area of 132 million square kilometres and thus involved around half of the total area of the high seas. Ships outfitted for catching squid operated intensively near the boundaries of the territorial waters of Peru, Argentina and Japan. Deep-sea fishing, on the other hand, concentrated on the regions around Georges Bank in the northwest Atlantic, areas of the northeast Atlantic, and to a smaller degree in the central and western Pacific. The monitored ships spent an average of 141 days at sea before sailing back into a port.

- It is difficult to quantify the amount of damage being inflicted by the increasing fishing pressure in international waters. One reason for this is that there are no reliable stock and reproduction statistics for many species, especially for exclusively deep-sea species. Another is that it is not clear how many fish the deep-sea fleets actually catch in many areas. In 2018, according to the estimates of Sea Around Us, three per cent of the global catches came from deep-sea areas.

To help curtail overfishing in various international waters and avoid resource conflicts, many nations have now established regional fisheries management organisations (RFMOs). These institutions develop collective rules and regulations for fisheries in their respective areas and are responsible for their implementation. The FAO therefore grants them a deciding role in the protection and management of natural stocks, primarily because it is the responsibility of the RFMOs to decide whether or not to adopt the voluntary FAO guidelines or recommendations for action in the particular RFMO area. Whether the individual RFMOs actually fulfil the roles of stock guardian and protector prescribed to them cannot be determined with certainty. Although reviews and surveys of the organizations are now regularly carried out and the results published, a current evaluation procedure for all RFMOs based on scientific standards does not exist.

When experts from Pew Charitable Trusts reviewed the work of three regional fisheries management organizations in 2019, they came to the conclusion that, among other things, all three bodies

- had implemented too few of the international guidelines, especially those that were aimed at putting an end to overfishing and at the recovery of stocks,

- required too much time to introduce new, modern management strategies and

- failed in the task of building a consensus among their member states on key issues of fisheries management.

- 3.18 > Deep-sea fishing would be an unprofitable business in many parts of the world if the fishery nations did not subsidize their fleets with an estimated USD 4.2 billion per year (value for the year 2014). This sum is around twice as much as the profits that the deep-sea fisheries would generate without government aid. The profitability of fisheries on the high seas depends on the individual states, the region of operations, the targeted species and the distance from ports. As the figure illustrates, primarily the South Korean, Taiwanese, Chinese and Russian fisheries would suffer significant losses without government support.

- Critics of industrial deep-sea fishing therefore doubt that stocks on the high seas can be effectively protected as long as economic and, in part, strategic interests are of uppermost importance, and as long as some states subsidize their deep-sea fleets with more than USD 13 billion per year. Subsidies are defined as direct or indirect financial contributions, mostly from government institutions, that result in lower fishing costs, more catches or a higher profit margin. These include, among others:

- contributions for the construction of new ships or the repair of vessels already in operation,

- government financing for the construction of new fishing harbours or technical improvements to existing facilities,

- tax relief for fishing businesses,

- fishery development programmes and

- fuel-price reductions.

- In 2016, for example, an analysis of global deepsea fishing revealed that without government financial support, fishing in more than half of the high-seas areas being targeted would not have been economically feasible. This means that without subsidies many concerted activities that create excessive fishing pressure would not even be happening. This is especially true for trawler fishing in the deep sea and for a large proportion of the squid capture in international waters. Still the governments pay, albeit in differing measure. The deep-sea fisheries of Japan are most heavily subsidized, followed by Spain, China, South Korea and the USA. Amazingly, for all five of these countries, the total contributions by far exceed the total income from deep-sea fisheries. The only really profitable targets on the high seas, according to calculations by scientists, are the high-priced predators such as sharks and tuna.

- 3.19 > An oyster farm on the coast of the US state of Maryland. Breeding of the American oyster is strictly regulated. In addition, scientists and farmers are working together to restore the natural stocks of this important water filterer.

- If scientific calculations show that fishing on the high seas is not profitable, why do countries continue to do it? The researchers believe that the businesses actually do make a profit in the end, for example, by catching and selling more fish than they report to the authorities. In addition, costs can be reduced by transferring the catches to reefer ships while still at sea, which prolongs the period of time that the fishing vessel can continuously remain at sea. Another possibility is that the ship’s crew is either poorly paid, or not paid at all.

Countries like China and Russia also use deep-sea fishing to pursue foreign policy interests. This is exemplified by the fishing operations of these two nations in Antarctic waters. Claiming the rights to resources in the Southern Ocean and showing a presence there is more important than the question of whether the fishing is economically profitable. And finally, it is probably also worthwhile to fish sporadically in regions that have not been fished or only sparsely fished in the past.

Here again, a negative example is provided by Chinese fishers, who cast their nets and lines on a massive scale near the boundaries of the marine protected area of the Galapagos Islands during tuna season. In the summer of 2020, 243 Chinese vessels cruised through the ecologically sensitive region, more than in any year previously. Beside vessels suspected of illegal fishing, the fleet also included reefer ships for transferring the catches on the high seas. The native Ecuadorian fishers could only watch helplessly as the biosphere was plundered. They themselves have fishing inspectors on their ships who monitor the catches and ensure that rare species are protected. The Chinese fleet, however, operates outside of the international public eye.

In 2017, when the Ecuadorian coast guard stopped a Chinese reefer ship inside the marine protected area and opened its container, the soldiers discovered around 6000 deep-frozen sharks, including endangered species such as hammerheads and whale sharks. Cases like these highlight the need for clear political commitment from all parties involved and effective implementation of and compliance with all directives and agreements. Without these, the promises of protection for the ecosystems of the high seas will be no more than empty words.

Is abstinence the only solution?

Critics of industrial fisheries are therefore appealing for a global shift in consumer attitudes. Marine conservation organizations argue that every thoughtless seafood meal contributes to a sell-out of the oceans. Like meat, wild-caught marine fish should be viewed as an exceptional delicacy in industrialized nations such as Germany, and only occasionally served. And when it is, it should come from sustainable, regional coastal fisheries. Fish that are transported around the world before being consumed, according to their rationale, do little to contribute to a sustainable way of life.

For the populations in poorer countries and on Pacific islands, on the other hand, fish is a necessary dietary staple. Because there are few inexpensive alternatives, these people are very dependent on fish as a source of protein. For the world’s oceans to provide sufficient food in the future for the Earth’s growing population, fish resources must be fairly distributed. A crucial aspect of this will have to be less fish and seafood consumption for those who can afford and have access to alternatives. Furthermore, according to the FAO, 35 per cent of the production of fisheries is still going to waste either because refrigeration-chain and hygiene regulations are not observed, buyers are not found for some products, or the buyers do not eat their purchases. The waste percentage is particularly high in North America and Oceania, where around half of the fish caught are ultimately not consumed.

Other voices advocate for designating at least 30 per cent of all marine space as protected areas, and for prohibiting direct human intervention of any kind in these regions, in order to offer a refuge for marine biological communities. There is a long list of convincing arguments for such measures. In marine protected areas there is a very good chance of recovery for previously heavily fished stocks. Biodiversity is generally high or even increases after protection status is declared. Moreover, many species reproduce more successfully because sexually mature animals are not caught, or spawning sites on the seafloor are not destroyed by bottom trawling. Marine protected areas, sometimes referred to as kindergartens or seed banks, also contribute to the recolonization of adjacent marine regions and the more rapid recovery of endemic stocks there.

- Furthermore, the biological communities in marine protected areas exhibit a greater resistance to the impacts of climate change, which is why many environmentalists and scientists see this strategy as the best solution.

The fish trade, in turn, relies on products from certified, sustainable fisheries – for example, those that meet the criteria and have been certified by the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC). In the past 20 years the MSC has awarded its blue sustainability seal to around 300 fisheries. It is the only internationally recognized certificate for sustainable wild-fish capture, although many individual countries also have their own national certification and inspection procedures for sustainable fishery products. In Germany, for example, these include Naturland Wildfisch, Followfish and Dolphin Safe.

Catches from MSC-certified fisheries, or those that are under MSC review, now make up 15 per cent of the official worldwide landings. The growing number of certified fisheries highlights the customers’ and retailers’ wish for sustainably produced products, and promises success in convincing the fisheries to improve their fishing operations and to have these efforts confirmed by a label.

Many of the certified fisheries were forced to make adjustments on behalf of marine conservation before they were able receive the label. For the most part, the changes were aimed at reducing direct consequential damages to the marine habitat by the fishery. Independent evaluations by experts have shown that MSC-certified fish stocks not only exhibit a larger biomass, but that the stocks also grew after certification.

- 3.20 > The snow crab is one of the most important target species of Japan’s fisheries. Scientists therefore monitor its stocks by means of annual research catches and related stock modelling.

- However, experts advise caution in interpreting this positive trend as evidence of an overall improvement in worldwide fishery practices. An MSC certification is not an all-purpose, end-all weapon in the fight against overfishing. For one thing, the effort and costs required by the process are so great that smaller fisheries are often unable to afford them. For another, environmentalists feel that the MSC regulations actually do not go far enough. Until recently, for example, certified fisheries were permitted to employ sustainable techniques on the same fishing trip with more traditional, destructive fishing techniques, such as bottom trawls, without losing their certification. Environmentalists have also accused the MSC of ignoring evidence that the certified companies are involved in the shark-fin trade or, in violation of MSC regulations, that they surround schools of dolphins in order to capture the tuna hunted by the marine mammals. Such operations generally result in the death of a large number of dolphins.

In order to prevent these practices in the future, a consortium of environmental organizations has submitted a list of 16 core demands to the MSC, with the hope that these will be considered in the current revisions of the MSC regulations. These include, among others, the need to ensure that

- the overall ecological footprint of the fishery activities of a certified company is assessed, including the non-certified portions;

- the fishers are no longer permitted to employ non-certified fishing techniques, for example, those that would lead to unnecessary bycatch;

- all fish species caught, including those in the bycatch, are subject to sustainability criteria and overfishing is prohibited;

- MSC-certified operators are no longer permitted to employ bottom trawls in marine regions with highly sensitive biological communities.

3.21 > With bottom-trawl fishing in the deep sea it is hard to predict which species will end up in the net. Here is a small selection of animals that were brought up in survey catches by New Zealand scientists at 1200 metres depth.

3.21 > With bottom-trawl fishing in the deep sea it is hard to predict which species will end up in the net. Here is a small selection of animals that were brought up in survey catches by New Zealand scientists at 1200 metres depth.- It remains to be seen whether the MSC will consider these recommendations.

In coastal regions where fishing is only practised by artisanal fishermen and -women, involving the local stakeholders in management decisions and giving them the responsibility for implementation and monitoring of the mutually agreed rules has paid off in many places. This stewardship or co-management process relies on the fishers to manage the resources in a sustainable way, because they have the exclusive right of use and thus a strong personal interest in protecting the marine ecosystem.

But such community-based, cooperative management approaches only function effectively where the number of participating stakeholders is small, where there is a high degree of collective unity, where all participants pursue the same interests and where the individual rights of use may not be sold to outside investors. Yet even if these conditions are met there is still a need for state oversight. Any policy solutions must also be tailored to the local conditions. Experience has shown that attempts to apply the same management strategies everywhere are likely to fail.

In its fisheries report published in 2020, the FAO emphasised that, in view of the increasing number of overfished stocks, the goal of putting an end to overfishing in the oceans by 2020 has not been met. The international community is therefore called upon to:

- show a stronger political will, especially at the national level;

- invest in improvements in fisheries management;

- promote the transfer of technology and knowledge, especially with regard to science-based fisheries management;

- limit fishing activities to levels that do not endanger the reproduction of fish stocks;

- influence the purchasing behaviour of consumers through information campaigns or effective marketing; and

- develop global fishery and marine monitoring systems, and make all of the data available to the public in a timely and transparent way.

- According to the FAO, developments in recent decades have proven that fishing pressure has been most successfully reduced in marine regions where regulations have been implemented and compliance monitored. In Argentina, Chile and Peru, for example, the proportion of overfished stocks sank from 75 per cent in the year 2000 to 45 per cent in 2011. Today, in the USA, there are only half as many overfished stocks as there were in the year 1997.

Other examples of success have been realized in the waters of Iceland and Norway, by the crab-diver fishery of Chile, which has become limited to artisanal fishers, in the waters of the coral triangle, and in the waters of Japan where the formerly overfished populations of the snow crab (Chionoecetes opilio) have recovered.

But in areas without a functioning fisheries management plan, according to the FAO, the situation for fish stocks is dire. Around three times more fish are caught in these areas than in intensively monitored regions of the sea. In addition, the stocks are often only half as large, and are generally in very poor condition. For this reason, the degree of success that sustainable fisheries management is now bringing for a number of countries has not been sufficient to halt the general worldwide decline of marine fish stocks. It is thus essential to learn globally from one another, share knowledge of successful and effective fisheries management strategies, select approaches that take local conditions into account, and implement them in close cooperation with the local populations.