Illegal fishing

Unscrupulous fishing worsens the problems

Nowadays, the world’s fish stocks are not only under threat from intensive legal fishing activities; they are also at risk from illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing. It is difficult to estimate precisely the total catch from pirate fishing. Researchers are engaged in the painstaking process of collating data from various countries’ fisheries control agencies, experts’ estimates, trade figures and the findings of independent research expeditions in order to arrive at an approximate figure for the total IUU catch. As this is a black market, however, estimates are bound to be unreliable. Some experts put the annual figure at around 11 million tonnes; others suggest that it may be as high as 26 million tonnes – equal to 14 or 33 per cent respectively of the world’s total legal catch (fish and other marine fauna) in 2011. These catches are additional to the world annual catch of fish and other marine fauna, currently 78.9 million tonnes.

For many years, however, too little account was taken of IUU fishing in estimates of fish stocks. This is problematical, for unless the IUU share is factored into the calculations, the legal catch quotas for a given maritime region cannot be determined correctly. Based on the assumption that less fish is being caught than is in fact the case, experts overestimate the size of the stock and set the following year’s catch quotas too high, potentially entrenching and accelerating the overexploitation of the stock. IUU fishing also exacerbates the problem of overfishing because IUU vessels even operate in marine protected areas where a total fishing ban has been imposed. It also pays little or no heed to fisheries management plans which are intended to conserve overexploited or depleted stocks.

However, the main reason why IUU fishing is a particularly critical issue today is that many fish stocks have already been overexploited by legal fishing activities. IUU fishing therefore puts fish stocks under additional pressure. If stocks were being managed sustainably, on the other hand, IUU fishing would no longer exacerbate an already difficult situation to the extent that it does today.

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) defines three categories of IUU fishing:

- ILLEGAL FISHING refers to fishing activities conducted by foreign vessels without permission in waters under the jurisdiction of another state, or which contravene its fisheries law and regulations in some other manner – for example, by disregarding fishing times or the existence of the state’s protected areas. For example, some IUU vessels operate in waters under the jurisdiction of West African states. As these countries generally cannot afford to establish effective fisheries control structures, the IUU vessels are able, in many cases, to operate with impunity.

- UNREPORTED FISHING refers to fishing activities which have not been reported, or have been misreported, by the vessels to the relevant national authority. For example, some vessels harvest more tonnage than they are entitled to catch under official fishing quotas. In 2006, for example, several Spanish trawlers were inspected by the Norwegian Coast Guard near Svalbard (Spitsbergen). The trawlers were found to hold not only the reported catch of headed and gutted cod but also a total of 600 tonnes of cod fillets which had not been reported to the Norwegian authorities. The Norwegian authorities subsequently imposed fines on the Spanish trawler company equivalent to 2 million euros.

- 3.24 > A chase at sea near South Korea: an entire fleet of illegal Chinese fishing vessels attempts to evade the South Korean Coast Guard. The fishermen were arrested by armed units soon afterwards.

- UNREGULATED FISHING refers to fishing activities in areas where there are no applicable management measures to regulate the catch; this is the case in the South Atlantic, for example. The term also applies to fishing for highly migratory species and certain species of shark, which is not regulated by a Regional Fisheries Management Organization (RFMO). And finally, the term applies to fishing activities in international waters in violation of regulations established by the relevant RFMO.

Although unregulated fishing is not in fact illegal under the law of nations applicable to the high seas, it is nonetheless problematical. It results in additional fish being caught over and above the maximum catches agreed by RFMO member states for their respective regions.

As a result, fully exploited stocks can easily become over-exploited. Furthermore, IUU fishermen often ignore the existence of marine protected areas established by the Regional Fisheries Management Organizations to support the recovery of overexploited stocks.

Why does IUU fishing exist?

From the fishermen’s perspective, IUU fishing is highly attractive as they pay no taxes or duties on these catches. A further reason why IUU fishing takes place on such a large scale is that it can often be practised with impunity. This is mainly the case in the territorial waters or exclusive economic zones of countries which cannot afford to set up costly and complex fisheries control structures such as those existing in Europe.

The situation is especially difficult in the developing countries. In a comprehensive analysis of IUU fishing worldwide, researchers conclude that IUU fishing is mainly practised in countries which exhibit typical symptoms of weak governance: large-scale corruption, ambivalent legislation, and a lack of will or capacity to enforce existing national legislation.

The Sub-Regional Fisheries Commission (SRFC), comprising seven member states in West Africa (Cape Verde, Gambia, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Mauritania, Senegal and Sierra Leone), has produced a detailed list of the various causes of IUU fishing:- There are insufficient and inadequately trained personnel in the relevant authorities.

- The authorities’ motivation to invest in relevant personnel is poor. Financially weak states set other priorities.

- Salaries are low, and vessel owners take advantage of this situation to make irregular payments to observers/ fisheries administrators to cover up their activities.

- The purchase, maintenance and operational costs of patrol boats and aircraft are very high. For effective control, there must be sufficient time spent out at sea or in the air. However, in some states, even though they are available, they are not operational due to logistical problems – lack of fuel, proper maintenance regime, etc.

- 3.25 > Transshipment is typical of IUU fishing. As seen here off the coast of Indonesia, smaller fishing vessels transfer their illegally caught fish onto larger refrigerated transport ships (reefers). The fishing vessels are restocked with fuel and supplies at the same time, enabling them to remain at sea for many months.

Where does IUU fishing take place?

The situation off the coast of West Africa is particularly critical. Here, IUU fishing accounts for an estimated 40 per cent of fish caught – the highest level worldwide. This is a catastrophe for the region’s already severely overexploited fish stocks. Confident that as a rule, they have no reason to fear any checks by fisheries control agencies or prosecution, some IUU vessels even fish directly off the coast – in some cases at a distance of just one kilometre from the shore. A similar situation exists in parts of the Pacific. Indonesian experts report that it is extremely difficult to track the whereabouts of IUU vessels around the country’s islands and archipelagos. The volume of the illegal catch here is correspondingly high, amounting to 1.5 million tonnes annually. The Arafura Sea, which lies between Australia and Indonesia, is also very severely affected. After West Africa, the Western Central Pacific Ocean is the region with the highest rate of IUU fishing worldwide. In the Western Pacific, IUU fishing accounts for 34 per cent of the total catch.

A similar situation exists in the Northwest Pacific Ocean, especially in the West Bering Sea. Here, IUU fishing is mainly practised by China and Russia and amounts to 33 per cent of the catch. Figures for the Southwest Atlantic are unreliable, but experts estimate that IUU fishing here amounts to 32 per cent.

What’s the catch?

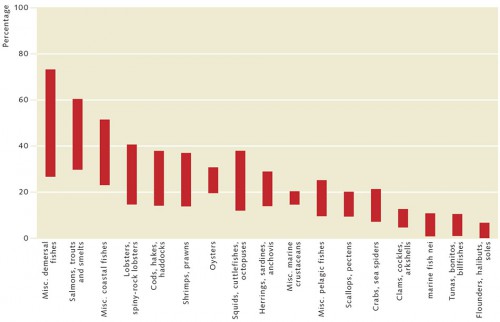

IUU fishing often targets high-value demersal species (i.e. those which live and feed on or near the bottom of the sea) such as cod, as well as salmon, trout, lobster and prawns. It is mainly interested in species which are already overexploited by legal fishing or which are subject to restrictions for fisheries management purposes. As these species can only be traded in small quantities, demand and prices are high – making this a lucrative business for IUU fishermen.

Too many loopholes

Combating illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing at sea is generally extremely expensive and very complex. Affluent countries such as Norway can afford to enforce stringent controls in the waters under their jurisdiction and deploy a large fleet of vessels and a great many personnel for this purpose. An effective and possibly less costly alternative is to carry out rigorous checks in port. However, this only helps to curb IUU fishing if all ports cooperate.

In the European Union (EU), regulations in force since 2008 and 2009 contain uniform provisions on the type of controls to be carried out in EU ports. Since then, it has become very difficult for IUU vessels to land their catches in EU ports.

Nonetheless, there are still ports in other regions where IUU fishermen can land their illegally caught fish with no repercussions. Here too, it is mainly the developing countries, with their absence of controls, which are particularly suitable for illegal transshipment. However, examples such as the Spanish trawlers near Svalbard show that even fishermen from EU countries are not immune to temptation and that the prospect of a healthy profit may persuade them to fish illegally.

The problem is exacerbated by the fact that not every IUU vessel needs to put into port in order to land its catch immediately. In many cases, especially off the coast of West Africa, the smaller fishing vessels load their catch onto larger refrigerated ships (known as reefers) while at sea. During this transshipment, fishermen on board are also resupplied with food and fuel, enabling them to remain at sea for many months.

- 3.26 > Different species groups (fish and other marine fauna) are affected by IUU fishing to varying degrees. One particular study has shown that from 2000 to 2003, IUU fishing mainly targeted demersal species (i.e. those which live and feed on or near the bottom of the sea). The figure shows the illegal and unreported catch, as a percentage of reported catch, by species group.

- The Sub-Regional Fisheries Commission (SRFC) concludes that some IUU vessels off West Africa are in operation 365 days of the year, putting massive pressure on fish stocks. The refrigerated ships then make for ports in countries with lax controls, enabling them to land their catches unhindered.

The practice of using a flag of convenience (FOC) also makes it easier to engage in IUU fishing activity. Instead of registering the ships in the shipping company’s home state, IUU fishers operate their vessels under the flag of another state, such as Belize, Liberia or Panama, with less stringent regulations or ineffective control over the operations of its flagged vessels.

By switching to a foreign register of ships, restrictive employment legislation and minimum wage provisions in the home country can also be circumvented, allowing the shipping companies to pay lower wages and social insurance contributions for their crews than if the vessel were registered in Germany, for example. Furthermore, fisheries legislation in “flag-of-convenience” states is often extremely lax. These countries rarely, if ever, inspect their vessels for illegal catches.

Monitoring of onboard working conditions is also inadequate, and conditions are correspondingly poor. The fishermen work for low wages on vessels whose standards of accommodation are spartan in the extreme, and which rarely comply with the current safety standards applicable to merchant shipping under the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS regulations). The Convention contains exact details of equipment that must be available to ensure safety on board.

Combating IUU fishing

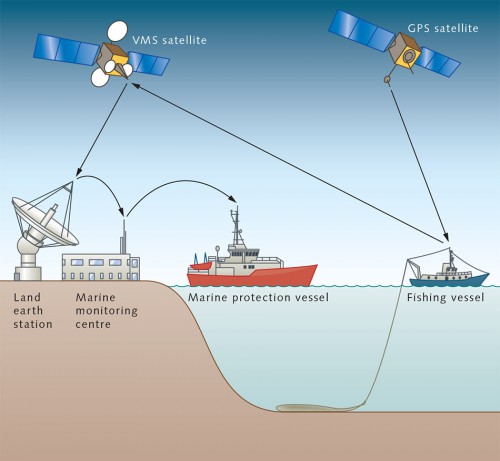

Today, IUU fishing is a global problem, with vast amounts of fish being caught illegally. Nonetheless, the worst seems to be over. IUU fishing was at its peak in the mid 1990s. Since then, according to the FAO, it has declined in various maritime regions, partly due to more stringent government controls. In Mauritania, for example, fisheries control structures have been established with support from German development assistance, with ships now being tracked by a satellite-based vessel monitoring system (VMS).

Other countries are now more inclined to comply with the relevant laws and agreements. Poland is a good example. For many years, Polish fishermen were constantly in breach of the EU’s quotas for cod fisheries for the eastern Baltic, routinely catching far more fish than the total allowable catch. This was tolerated by the Polish government of the day. With the change of government in November 2007, however, the situation changed, and Poland is now complying with the quotas.

World population growth is likely to drive up the demand for fish even further. IUU fishing will therefore continue to be an attractive option, and can only be curbed with more stringent controls. To that end, controls and sanctions must be coordinated and consistently enforced at the international level. The FAO therefore adopted the Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries (CCRF) in 1995, which was endorsed by around 170 member states. Although the CCRF is voluntary and non-binding, a number of countries, including Australia, Malaysia, Namibia, Norway and South Africa, have incorporated some of its provisions into national law. Predictably, IUU fishing has decreased in these regions.

3.27 > An armed unit of the South Korean Coast Guard arrests Chinese fishermen who have been fishing illegally in South Korean waters. Very few countries can afford such effective fisheries control structures.

3.27 > An armed unit of the South Korean Coast Guard arrests Chinese fishermen who have been fishing illegally in South Korean waters. Very few countries can afford such effective fisheries control structures.- In order to prevent landings of illegally caught fish in the EU, Council Regulation (EC) No 1005 on IUU fishing was adopted in 2008; this was followed by Council Regulation (EC) No 1224 establishing a Community control system for ensuring compliance with the rules of the common fisheries policy in 2009. These regulations describe in precise detail which vessels may land fish in the EU, which specific documents they must produce, and how the catch is to be controlled. The aim is to prevent IUU fishing EU-wide and close any loopholes. The current procedure for landing catches in an EU port is therefore as follows:

A) Before the vessel lands its catch, it must provide reasonable advance notice.

B) Once the vessel has docked,

- the fishing licence is checked. This includes the vessel’s operating licence issued by the flag state and information showing who is authorized to operate the vessel.

- the fishing authorization is checked. This contains detailed information about the vessel’s permitted fishing activity, including types of fish, times, locations and quantities.

- the catch certificate is checked. This contains information about the catch currently on board, including where and when it was caught.

- the logbook in electronic format is checked. The master of the vessel must record on a daily basis when and where the fish was caught, and in which quantities.

- If a ship lacks any of the relevant documentation, it is not permitted to land its catch and must head instead for a port outside the EU. Permission to land the catch is also refused if there are any discrepancies between the figures given in the catch certificate and the daily entries in the electronic logbook. In this case, the fisheries control agency – in Germany, this is the Federal Office for Agriculture and Food – may require vessel monitoring data to be produced. Nowadays, electronic devices, or “blue boxes”, are installed on board fishing vessels and form part of the satellite-based vessel monitoring system (VMS). The blue box regularly sends data about the location of the vessel to the fisheries monitoring centre (FMC) responsible for the area where the vessel is currently fishing. If the vessel enters territorial waters or fishing grounds where it is not permitted to fish, the master of the vessel can be prosecuted.

- 3.28 > Nowadays, fishing vessels must be equipped with electronic devices, or “blue boxes”, which form part of the satellite-based vessel monitoring system (VMS). The blue box regularly sends data about the location of the vessel to the fisheries monitoring centre (FMC). Vessels are also equipped with GPS transmitters which track the ship’s speed and position.

- In suspicious cases, the state in which the fish is to be landed may request the VMS data from the state in whose waters the vessel has been fishing. Furthermore, the landing procedure is observed in each EU port. The fisheries control agency checks how much is being landed and which species comprise the catch. Random checks are also carried out periodically. Relevant measures have been agreed by the EU and the other countries belonging to the North East Atlantic Fisheries Commission (NEAFC), including Iceland and Norway, putting this region beyond the reach of IUU fishermen.

The same applies to the Northwest Atlantic, ports in the US, Canada and other member states of the Northwest Atlantic Fisheries Organization (NAFO), such as Denmark, Iceland and Norway. The example of Mauritania shows that more stringent controls can be introduced to good effect in developing countries as well. VMS-based monitoring of vessels and controls of landings in port have largely eliminated IUU fishing here.

The FAO has been lobbying for many years for stringent and uniform controls worldwide and is a firm advocate of close cooperation among ports. It takes the view that a concerted approach by ports will make it more difficult for IUU fishing vessels to find a port where they can land their catches without fear of repercussions. However, ports derive an income stream from the charges they impose on vessels using their facilities. Ports which are used by a large number of vessels generate very large amounts of revenue, and for some ports, this takes precedence over the protection of fish stocks. Although a draft Agreement on Port State Measures to Prevent, Deter and Eliminate Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated Fishing has existed for a good three years, based on the FAO Code of Conduct, no specific measures to enforce global action have been adopted yet.

A further initiative to combat IUU fishing consists of the blacklists held by the RFMOs. These include details of vessels which have attempted at some point to land IUU fish at an RFMO port. Port and fisheries control authorities regularly refer to these blacklists. This “name and shame” policy is intended to make it even more difficult for IUU vessels to find ports where they can land their catches. However, here too, states must be willing to cooperate in order to combat IUU fishing effectively. As long as the lack of international coordination allows loopholes to exist, IUU fishing will continue.