Diversity at risk

Are fish species facing extinction?

Although many stocks have been overfished by industrial fisheries, as a rule this does not result in the extinction of fish species. The classical notion of a species being wiped out by human activity, like the case of the dodo, a flightless bird on the island of Mauritius, cannot be directly applied to fisheries. There is an economic reason for this: long before the last fish is caught it would become unprofitable to fish for it, so it would no longer be pursued by the fishery in the affected region. Specialists refer to this kind of situation as commercial depletion.

Some fish stocks have been reduced by 50 to 80 per cent in the past. This would spell extinction for many terrestrial animals, especially for species that produce small numbers of offspring. The death of even low numbers of young animals by disease or predation could then completely wipe out such a species. This is not the case with fish. As a rule, the stocks recover. One important reason for the resilience of fish stocks is their high reproductive capacity. Cod can produce up to 10 million eggs each year. An additional factor is that a fish species is usually represented by multiple stocks.

- 1.11 > Animal conservationists have been trying for several years to reintroduce the sturgeon to German waters. A number of the animals released have yellow markers on their backs. Fishermen who catch one of these are requested to report the number on the marker to the conservation group and return the fish to the water.

- There is no question that intensive fishing has severely reduced the amount of fish, the fish biomass, in many marine regions. The higher trophic levels are especially affected. The large fish have been and still are the first to be depleted. But even these are usually not in danger of biological extinction. In order to draw conclusions about the status of a fish species, all of its stocks have to be assessed. For several years there has been some controversy about the best mathematical and statistical models to use for this.

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) has established a general classification system. It classifies fish stocks as overexploited, fully exploit-ed and non-fully exploited. According to the FAO, almost 30 per cent of all fish stocks are considered to be overexploited. As a rule, however, the species will be preserved.

Regrettable exceptions

There are, however, exceptions. Some species of tuna fish bring such high prices on the market that catching them is profitable even when their numbers are very limited. One fish can weigh up to 500 kilograms. Certain species, such as the bluefin tuna (Thunnus thynnus), which lives in the Atlantic, can bring a price of 100 dollars per kilogram. In Japan, hundreds of thousands of Euros may be paid for the first or best tuna of the season. Expensive fish is a mark of prestige there. Furthermore, the first tuna of the season are considered to be bringers of good luck, for which some customers will pay a lot of money. For practical purposes, fishing for such valuable specimens can be compared with hunting rhinoceroses on land. As late as the 1920s bluefin tuna still appeared regularly in the nets of Norwegian mackerel fishers. Today this species has completely dis-appeared from the Kattegat and the North Sea. And in the Atlantic there are only very small numbers of bluefin tuna remaining.

- 1.12 > Around the year 800 the European sturgeon was indigenous to many rivers and almost all of the coastal areas of Europe. Since then its marine distribution has shrunk significantly, and it is now limited to the region between Norway and France. The only remaining spawning area of the European sturgeon is the Gironde Estuary in France.

- Other species of fish are threatened with extinction because they are under multiple pressures at the same time, both from fisheries and destruction of their habitats. One example is the European sturgeon (Acipenser sturio), whose distribution once extended from southern Spain to eastern Europe. The sturgeon spawns in rivers and grows to sexual maturity in the sea. Like salmon, the European sturgeon migrates back into the rivers to spawn. The species once inhabited the Eider, the Elbe, and small north German rivers like the Oste and the Stör. But over the past hundred years the stocks have greatly declined. Today there is only one remaining stock in Europe, in the Gironde Estuary in southwest France, but it has also been shrinking in recent years.

1.13 > The dodo died out at the end of the 17th century. Native exclusively to the islands of Mauritius and Réunion, the flightless bird had no natural predators before the arrival of humans. It was completely wiped out by imported rats, monkeys and pigs.

1.13 > The dodo died out at the end of the 17th century. Native exclusively to the islands of Mauritius and Réunion, the flightless bird had no natural predators before the arrival of humans. It was completely wiped out by imported rats, monkeys and pigs.- The decline of the sturgeon has multiple causes: river training, installation of weirs, pollution of the water, and fishing. Today, the remaining animals are threatened primarily with ending up in fishing nets as unintentional bycatch. The European sturgeon is classified as “Critically Endangered” on the Red List of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). The release of juvenile individuals to rivers has therefore been ongoing for several years, in order to re-introduce the species into its various native regions of Europe, including Germany. In addition, attempts are being made to encourage the fish to spawn in their once-native waters by returning some stretches of river to their natural state or building fish steps around weirs. It is still uncertain whether these efforts can save the European sturgeon.

Some species of seahorse are also subject to multiple threats – including pollution of the seas and destruction of their habitats, the mangroves. There is also a large demand for them. They are fished on coral reefs, in mangroves or seagrass beds, and are sold as traditional medicine on Chinese markets and as ornamental fish for aquariums. There are breeding programs, in Vietnam for example. But still, according to the IUCN Red List, of 38 worldwide seahorse species seven are considered “endangered” and one even “critically endangered”. The species primarily at risk are those that occur in a small, relatively limited geographic area. These are referred to as endemic species. Examples such as these illustrate that humans need to be more responsible in using and protecting fish resources in the future. The fact remains, however, that for most fish species in the world there is no danger of extinction. The IUCN list was originally established for land organisms. These generally do not have the reproductive capacity of fish. Critics therefore say that the risk of extinction expressed in IUCN standards is exaggerated for many commercial fish species.

Other marine animals are also affected

Not only do fisheries alter the natural species structure of the fish that are being fished for; they also have an impact on the stocks of animals that are taken as bycatch. U.S. researchers have calculated that at least 200,000 loggerhead sea turtles and 50,000 leatherback turtles worldwide were caught incidentally in the year 2000 by tuna and swordfish fishers. The turtles are caught on the hooks of “longlines”. These are usually several kilometres long and can be fitted with thousands of baited hooks. If the turtles snap at these they will be hooked. Some are able to free themselves and others are thrown live back into the ocean by the fishermen. But thousands die an agonizing death. Tests are now being carried out to shape the hooks so that the turtles will no longer be caught by them.

The longlines can also be fatal for albatrosses because they do not sink to the working depth immediately after being let out, rather they float for a while at the surface and attract the birds. Environmental organizations estimate that hundreds of thousands of sea birds are unintentionally killed annually worldwide by longline fishing. New methods are therefore also being tested by which longlines are deployed through tubes that extend up to 10 metres below the surface, so that albatrosses cannot see or reach the bait.

- 1.14 > This bluefin tuna, weighing 268 kilograms, fetched a price of 566,000 Euros at a fish auction in Tokyo in January 2012. It was bought by Kiyoshi Kimura (left), president of a sushi gastronomy chain. In early 2013, Kimura even paid a full 1.3 million Euros for a tuna. That translates into a price per kilogram of more than 6000 Euros.

- In the Baltic Sea, the harbour por-poise is also endangered as bycatch. There are only an estimated 500 to 600 individuals remaining in the eastern Baltic Sea. The harbour porpoise was hunted here for decades. Severe icy winters are also a strain on them. Today, every unintentionally caught animal brings the stock closer to extermination. It is a near tragedy that the eastern Baltic Sea harbour seals very rarely mate with their relatives in the North Sea and western Baltic Sea. The North Sea stock is comparatively large. Researchers estimate it to be around 250,000 animals. Because the eastern animals do not mate with their western relatives, it is feared that the species could die out in the Baltic Sea. This would mean a loss of species diversity in the region.

Genotype

Genotype refers to the total genetic information of an organism that is stored in the cell nucleus of each body cell. Among individuals of a species most of the genes are identical. But their combination is unique for every individual.Phenotype

The phenotype is expressed in the appearance of an individual: the observable characteristics of the individual genotype. Phenotypic attributes include eye colour, psychological traits, or genetically caused illnesses.The fisheries influence evolution

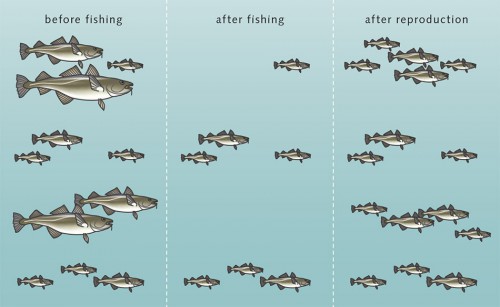

Intensive fishing, however, also changes the biological diversity in another way. Scientists are now discussing the phenomenon of fisheries-induced evolution. When the fisheries primarily catch large and older individuals, then, over time, smaller fish that produce offspring at an earlier age become more successful. The fisheries thus critically upset the natural situation. In natural habitats that are not affected by fisheries, larger fish that reach sexual maturity at a greater age are more dominant. Their eggs have lower mortality rates. The eggs and larvae can better survive phases of hunger in the beginning because they possess more reserve substance, more yolk, than the eggs and larvae of parents that reproduce at a younger age. The entire stock benefits from this because many offspring are regularly produced, which preserves the stock. Under heavy fishing pressure, on the other hand, the animals that primarily reproduce are those that are sexually mature at a smaller size. But they produce fewer eggs, and their eggs have higher mortality rates. Through computer models and analyses of real catch data, and using the example of the northeast Arctic cod, researchers have been able to show that this fish stock has actually undergone genetic alteration through time. Fish with the genotypic trait of becoming sexually mature at a young age and small body size have become more successful. This is true for both males and females. To illustrate this, the research-ers have employed catch data in their model that extend back to 1930 and document the gradual changes with respect to age, size, and reproductive capacity. The study was based on especially detailed data sets of the catches in Norwegian waters. Originally the northeast Arctic cod became sexually mature at an age of 9 to 10 years.

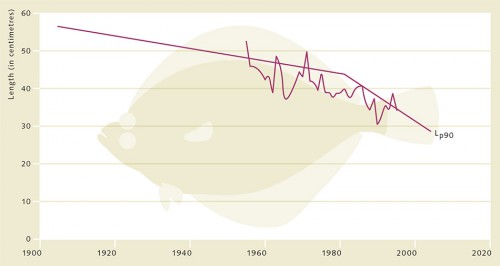

- 1.15 > Over decades of fishery, plaice in the North Sea that achieve sexual maturity with a smaller body size have gradually become predominant. This relationship can be clearly depicted by using different probabilities (p) in mathematical models. The body length (L) of 4-year-old plaice that will become sexually mature in the coming season with a 90 per cent probability (p90) is illustrated. As the graph shows, this body length (Lp90) has decreased significantly over recent years.

In the northeast Atlantic today, the cod is sexually mature at 6 to 7 years old. It is notable that this fisheries-induced evolution has occurred over a period of just a few decades. Experts feel that one reason for this is that the fisheries exert a much greater pressure than natural selection factors such as predators or extreme environmental conditions, such as heat or cold. The computer models also indicate that it would take centuries for the effects of the fisheries-induced evolution to turn around – even if the fisheries were completely stopped. In actual practice, the effects may even be irreversible. Within the past 10 years fisheries-induced evolution has been verified for a number of species, including the North Sea plaice.

The effect of fisheries is thus exactly the opposite of what an animal breeder usually aims for. The animal breeder, as a rule, selects the largest and most productive animals in order to continue breeding with them. As a result of the fisheries, by contrast, precisely those older and larger animals with the highest reproductive capacity are killed.

In the northeast Atlantic today, the cod is sexually mature at 6 to 7 years old. It is notable that this fisheries-induced evolution has occurred over a period of just a few decades. Experts feel that one reason for this is that the fisheries exert a much greater pressure than natural selection factors such as predators or extreme environmental conditions, such as heat or cold. The computer models also indicate that it would take centuries for the effects of the fisheries-induced evolution to turn around – even if the fisheries were completely stopped. In actual practice, the effects may even be irreversible. Within the past 10 years fisheries-induced evolution has been verified for a number of species, including the North Sea plaice.

The effect of fisheries is thus exactly the opposite of what an animal breeder usually aims for. The animal breeder, as a rule, selects the largest and most productive animals in order to continue breeding with them. As a result of the fisheries, by contrast, precisely those older and larger animals with the highest reproductive capacity are killed.

Genetic impoverishment in fish?

In proportion to their body size, large and mature fish invest relatively more energy into the production of eggs than small, young animals that have considerably less body mass and volume. Older fish thus provide a kind of reproductive insurance. As long as enough older fish are present, sufficient offspring will be produced. But in stocks that consist of few age groups, and primarily of younger age groups, the danger of offspring deficiency increases when the reproductive conditions intermittently worsen, such as times of food scarcity. Stocks in which older fish predominate can more efficiently withstand these kinds of fluctuations, because the mature ones will reli-ably produce offspring in the following season. Stocks comprising different age groups also exhibit greater resil-ience because the spawning season of the fish varies with their age. There are thus a sufficient number of spawning animals at any given time in a mixed stock. Periods of unfavourable environmental conditions therefore have a less severe impact.

- 1.16 > A fish stock before fishing, after fishing, and after reproduction. The changes in body size are a result of fisheries-induced evolution.

- Warnings are now being raised that fisheries can also cause genetic impoverishment, or “genetic erosion” in the species being fished. This phenomenon is also recognized in land animals. With the destruction of habitats like rain forests, the distribution areas of species become critically limited. Many individuals die before they can mate. In addition to the species-specific genetic material, every organism possesses a small share of individual genetic attributes. If the animal dies without producing offspring, these individual attributes are lost and the population is genetically impoverished. Extreme genetic erosion is referred to as a genetic bottleneck. In this case, a species is reduced to a small number of individuals. This could occur as the result of a natural catastrophe such as a vol-canic eruption or flooding. Intensive hunting of geographically restricted populations like the Siberian tiger can also lead to a genetic bottleneck. In extreme cases this leads to inbreeding. The animals produce offspring with genetic defects or that are susceptible to disease. Some scientists are concerned that genetic erosion leading to genetic bottlenecks occurs not only in land animals, but also in some fish species through overfishing. So far, however, this assumption is hypothetical and it is presumably not valid. For most of the commercially depleted fish stocks neither genetic erosion nor genetic bottlenecks can be statistically verified. Specialists believe that even fish stocks that have been commercially depleted still possess thousands of individuals capable of reproduction. The genetic variability thus probably remains great enough to preclude the erosion effects.

Slowing down fisheries-induced evolution

Experts recommend giving more attention to the ecogen-etic aspects of fishery management in the future. There is already a general consensus that fishery management should not consider a fish species independently of its habitat. Beyond this, however, ecogenetic models are necessary. These can be used to estimate which changes are caused by fisheries and to what degree genetic changes influence a stock, but also how these ultimately affect the future fishery harvests. Through responsible fishing, there is hope that fisheries-induced evolution can be reversed, or at least slowed down. It can probably not be completely stopped. Researchers also need to employ complex evolution models. Up to now, often only the age classes of a fish stock have been considered in detail for calculations of stock development. Fish sizes are entered into the calculation simply as the mean of an age class. This mean, in turn, has been calculated from long years of body-length measurements. An age class for a fish stock, therefore, always has a fixed, assigned average size. In fact, however, the mean size of an age class changes from year to year, depending mainly on the food supply. In years of scarce food supply immature animals grow more slowly. This variability has to be given greater consideration in the future. And, of course, there are always larger and smaller individuals within an age class. These fluctuations also have to be addressed. The mean value is not sufficient for an evolutionary model. Researchers therefore call for more intensive cooperation between fishery authorities, who have access to detailed data, and mathematicians and statisticians, who can develop powerful computer models.