![The battle for the coast – © [M], Beate Zoellner/Bildmaschine.de](https://worldoceanreview.com/wp-content/images/wor1/kapitel_03c_k.jpg)

The battle for the coast

The million dollar question: how bad will it be?

Climate change is placing increasing pressure on coastal regions which are already seriously affected by intensive human activity. This raises the question of whether – or to what extent – these areas will retain their residential and economic value in the decades and centuries to come, or whether they may instead pose a threat to the human race. Also, we do not know what changes will occur to the coastal ecosystems and habitats such as mangroves, coral reefs, seagrass meadows and salt marshes that provide the livelihood of coastal communities in many places. Scientists have tried in various studies over recent years to assess the extent of the threat posed by sea-level rise. To appreciate the coastal area at greatest risk of flooding, it is necessary to first analyse current heights above sea level. This is not easy because no reliable topographical maps yet exist for many coastal areas. At a rough estimate more than 200 million people worldwide live along coastlines less than 5 metres above sea level. By the end of the 21st century this figure is estimated to increase to 400 to 500 million.

- 3.12 > Bangladesh experienced the full force of Cyclone Aila in 2009. Thousands of people lost their homes. This woman saved herself and her family of five in a makeshift shelter after the gushing waters burst a mud embankment.

- During the same timeframe the coastal megacities will continue to grow. New cities will be built, particularly in Asia. In Europe an estimated 13 million people would be threatened by a sea-level rise of 1 metre. One of the implications would be high costs for coastal protection measures. In extreme cases relocation may be the only solution. A total of a billion people worldwide now live within 20 metres of mean sea level on land measuring about 8 million square kilometres. This is roughly equivalent to the area of Brazil. These figures alone illustrate how disastrous the loss of the coastal areas would be. The Coastal Zone Management Subgroup of the IPCC bases its evaluation of the vulnerability of coastal regions, and its comparison of the threat to individual nations on other features too:

- the economic value (gross domestic product, GDP) of the flood-prone area;

- the extent of urban settlements;

- the extent of agricultural land;

- the number of jobs;

- the area/extent of coastal wetlands which could act as a flood buffer.

- 3.13 > On the North Sea island of Sylt, huge four-legged concrete “tetrapods” are designed to protect the coast near Hörnum from violent storm tides. Such defence measures are extremely costly.

![Fig. 3.13 © [M], Beate Zoellner/Bildmaschine.de 3.13 > On the North Sea island of Sylt, huge four-legged concrete “tetrapods” are designed to protect the coast near Hörnum from violent storm tides. Such defence measures are extremely costly. © [M], Beate Zoellner/Bildmaschine.de](https://worldoceanreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/10/3_13-kuestenschutz-500x333.jpg)

Extra Info Climate change threats to the coastline of northern Germany

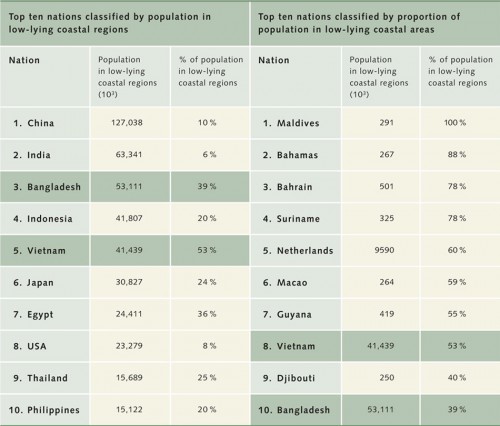

- A quite accurate estimate has now been made of which nations would suffer the most because a large percentage of the population lives in coastal regions. Bangladesh and Vietnam are extremely vulnerable. Nearly all the population and therefore most of the national economy of the low-lying archipelagos of the Maldives and the Bahamas are now under threat. In absolute numbers China is at the top of the list.

The most vulnerable regions in Europe are the east of England, the coastal strip extending from Belgium through the Netherlands and Germany to Denmark, and the southern Baltic Sea coast with the deltas of Oder and Vistula rivers. There are also heavily-populated, flood-prone areas along the Mediterranean and the Black Sea, such as the Po delta of northern Italy and the lagoon of Venice as well as the deltas of the Rhône, Ebro and Danube rivers.

Some densely-populated areas in the Netherlands, England, Germany and Italy already lie below the mean high-water mark. Without coastal defence mechanisms these would already be flooded today. For all these regions, therefore, the question of how fast the sea level will rise is extremely important and of vital interest. We need to resolve how we can intensify coastal protection right away, how society can adapt itself to the new situation, and whether it might even be necessary to abandon some settlements in the future. Without appropriate coastal protection, even a moderate sea-level rise of a few decimetres is likely to drive countless inhabitants of coastal areas in Asia, Africa and Latin America from their homes, making them “sea-level refugees”. The economic damage is likely to be enormous. The infrastructure of major harbour cities and especially regional trading and transportation networks – which often involve coastal shipping or river transport – would also be affected. Experts have prepared a detailed estimate of the implications of rising sea levels on Germany’s coastlines.

- 3.14 > The Netherlands is readying itself for future flooding. Engineers have constructed floating settlements along the waterfront at Maasbommel. Vertical piles keep the amphibious houses anchored to the land as the structures rise with the water levels.

![Fig. 3.15: © maribus (after Schrottke, Stattegger und Vafeidis, University of Kiel) 3.15 > Der Anstieg des Meeresspiegels wirkt sich auf die Küsten und ihre Bewohner unterschiedlich aus. Der Mensch kann sich durchaus mit Gegenmaßnahmen schützen. Die Kosten des Schutzes können aber beträchtlich sein und langfristig den Nutzwert übersteigen. Die Maßnahmen werden unterschieden in: [S] – Schutzmaßnahmen, [A] – Anpassungsmaßnahmen und [R] – Rückzugsmaßnahmen. © maribus (nach Schrottke, Stattegger und Vafeidis, Universität Kiel)](https://worldoceanreview.com/en/files/2010/10/3_15_anstieg_des_meeresspiegel_en-112x150.jpg) 3.15 > Rising sea levels impact differently on coastal areas and their inhabitants. Societies may take steps to protect themselves, but the costs can be substantial and ultimately exceed the benefits. The measures are classified as: [P] – Protective, [A] – Adaptive, and [R] – Retreat measures

3.15 > Rising sea levels impact differently on coastal areas and their inhabitants. Societies may take steps to protect themselves, but the costs can be substantial and ultimately exceed the benefits. The measures are classified as: [P] – Protective, [A] – Adaptive, and [R] – Retreat measuresAn old saying for tomorrow: Build a dyke or move away

Ever since first settling along the coast, human societies have had to come to terms with changing conditions and the threat of storms and floods. Over time they developed ways of protecting themselves against the forces of nature. Today four distinct strategies are used, none of them are successful in the long term:- Adaptation of buildings and settlements (artificial dwelling hills, farms built on earth mounds, pile houses and other measures);

- Protection/defence by building dykes, flood barriers or sea walls;

- Retreat by abandoning or relocating threatened settlements (migration);

- “Wait and see”, in the hope that the threat abates or shifts.

- 3.16 > Nations with the largest populations and the highest proportions of population living in low-lying coastal areas. Countries with fewer than 100,000 inhabitants are not included. Also excluded are 15 small island states with a total of 423,000 inhabitants.

- There are different strategies for combating and coping with the effects of rising sea levels.different strategies for combating and coping with the effects of rising sea levels.Whether a measure is used at a regional or local level depends mainly on the cost and the geological features of the area. In the Ganges-Brahmaputra delta region of Bangladesh for instance, heavy sea dykes would sink into the soft subsoil. Also, there is no money available to erect hundreds of kilo-metres of dykes. Such a project is likely to cost more than 20 billion euros – at least a hundred times more than the annual coastal defence costs of the Netherlands and Germany combined. The national economy of Bangladesh could not support anything like this amount. In other areas there are simply not enough building materials to protect the coast. Many coral islands do not have the sediment they need to hydraulically fill the coastline, or the space and building materials for dykes and sea walls. Even if enough cash were available, these islands would still be largely defenceless against the sea. The threat from rising sea levels is worsened by the fact that coralline limestone is being removed from the reefs and used to build hotel complexes.Further information on this topic is available here:

- It is impossible to foresee with any accuracy what the rising sea levels will mean for coastal and island nations and their defence in the 21st century, as this largely depends on the extent and speed of developments. If they rise by much more than 1 metre by 2100, then the dykes and protective structures in many places will no longer be high enough or stable enough to cope. New flood control systems will have to be built and inland drainage systems extensively upgraded. Experts anticipate that the annual costs of coastal protection in Germany could escalate to a billion euros – to protect assets behind the dykes worth 800 to 1000 billion euros. On a global scale the cost could be a thousand times greater. Although the costs of defence and adaptation would appear worthwhile to some nations in view of the substantial economic assets protected by the dykes, the poorer coastal areas will probably be lost or become inhabitable. The inhabitants will become climate refugees.

- Presumably the industrialized countries are capable of holding back the sea for some time using expensive, complex coastal protection technology. But even there, this strategy will ultimately have to give way to adaptation or even retreat. Extremely complex defensive fortifications such as the flood barriers of London, Rotterdam and Venice are likely to remain isolated projects. For most other areas the development of modern risk management conceptsthe development of modern risk management conceptswould be more logical.Further information on this topic is available here: