The coastal states’ responsibility

Each country must play its part

The exploration and exploitation of certain marine minerals on the deep ocean floor are governed by detailed regulations adopted by the International Seabed Authority (ISA). They also cover aspects of environmental protection. The exploitation of marine minerals in the international seabed area in future will thus be regulated by a uniform set of rules that are applicable worldwide. However, no such regime exists for the coastal states’ exclusive economic zones (EEZs) and continental shelves. Although the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) obliges every state party to protect and preserve the marine environment, it is a matter for each individual state to adopt its own detailed legislation on the use of its exclusive economic zone (EEZ), on marine mining on the continental shelf, and on the protection of the marine environment. However, as the ongoing pollution of coastal waters and disasters such as the Deepwater Horizon oil rig explo-sion show, this does not guarantee that the marine en-vironment will indeed be protected. And yet states have a particular responsibility, because the coastal waters within the EEZs are the world’s most intensively utilized marine areas, providing food and income for very large numbers of people. Over time, the pressure on the EEZs has increased. At one time, the coastal waters mainly supplied fish. During the last century, the tourism industry expanded and later, industrial sites were established along the coasts and oil and gas drilling rigs were installed on the continental shelf. Effluents from factories and intensive farming are still polluting coas-tal areas, and over the next five years, marine mining is likely to have a considerable impact as well, particularly the extraction of massive sulphides, which are mainly found on the continental shelf.

- 4.7 > A boy plays in a carpet of algae at the seaside in Qingdao in China. Excessive use of fertilizers is one of the causes of algal blooms. Coastal waters are being polluted elsewhere as well, despite international marine protection agreements.

Marine mining – controlled by governments

Given the very important role played by the marine environment and the range of pollutants to which it is exposed, states should be treating the marine areas under their jurisdiction with particular care. Indeed, UNCLOS contains comprehensive provisions to that effect. However, they are framed in very general terms, and countries have considerable leeway to decide how to transpose these provisions into national law. In some cases, national legislation does not adequately protect the sea from overexploitation and pollution. What’s more, not every country safeguards compliance with environmental legislation or regularly monitors its industrial enterprises. Although relevant legislation is in place, environmental pollution and degradation still routinely occur in many countries. For experts, therefore, the worry is that some countries could well adopt a similarly lax approach to marine mining on their continental shelves. They could even attract potential investors by offering them the chance to carry out mining operations with no obligation to achieve stringent and costly compliance with environmental regulations, and without having to worry about checks or inspections.

- 4.8 > In July 2010, a waste tank at a copper mine in the coastal province of Fujian in China burst open, spilling toxic slurry into a river and killing 1900 tonnes of fish.

Toothless legislation

A recent comparative analysis of the mining industry in the G20 states reveals the difficulties arising in the implementation of existing environmental legislation in some countries. The findings for the Latin American G20 countries Argentina, Brazil and Mexico are par-ticularly interesting. Although the study relates to on-shore mining, it identifies specific problems which are likely to affect marine mining in future as well. In all 3 countries, detailed regulations and standards for environmental protection are in place, but a number of central challenges stand in the way of robust compliance:- Government agencies tasked with overseeing the mining industry are poorly equipped with personnel, and there is also a shortage of skilled labour in some cases, as well as problems accessing funding. As a result, very few site visits or inspections of mines take place. Instead, assessments are generally confined to desk reviews of applications and documentation.

- Government agencies tasked with overseeing the mining industry are too close, either spatially or administratively, to political decision-makers. In some cases, assessors’ offices are located in regional government buildings, enabling politicians to exert influence over their activities.

- Even if the regulatory agencies are able to work independently, concerns are often ignored. Critical findings are not taken seriously or are disregarded by decision-making bodies, such as mining authorities.

- There are very few quality standards or certification schemes for consultancies that prepare environmental impact assessments, making it very easy for industrial enterprises to commission biased reports that gloss over the negative impacts of mining.

Following a good example?

Not everyone shares these concerns. In the view of some experts who specialize in the Law of the Sea, the ISA Regulations have established universally applicable standards of best practice for marine mining. Although these do not constitute binding regulations that must be incorporated into national legislation on deep-sea mining on the continental shelf, the ISA instruments serve, nonetheless, as a model to which coastal states must, at the very least, aspire. What’s more, if it trans-pires that a state is causing massive environmental damage on its continental shelf, it may face prosecution in an international court such as the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS); for example, legal proceedings may be initiated by neighbouring countries whose waters have been polluted.

Both cobalt-rich crusts and massive sulphides are mainly found on the continental shelves of island states that have no mining industry of their own. It is very likely that future mining operations here will be undertaken by international extraction industry companies on a contractual basis. It is not in these companies’ interests to destroy the marine environment on the state’s continental shelf, for if a company that causes such degradation were to apply for a licence to extract resources in the international seabed area in future, the ISA would be justified in refusing the application due to a lack of confidence in the company concerned – resulting in its loss of access to profitable seabed areas.

- 4.9 > A tanker’s useful life ends – and an oil disaster begins. In November 2002, the Prestige sank off the northwest coast of Spain, spilling around 60,000 tonnes of oil into the sea and polluting almost 3000 kilometres of French and Spanish coastline.

- A further relevant factor, in the view of some experts in the Law of the Sea, is that when selecting mining areas, mining multinationals will not necessarily give preference to unreliable states with lax legislation, for experience has shown that cooperation with these countries can be extremely problematical for the companies concerned. Negotiated contracts are not always complied with, and in politically unstable regions, there is also a risk of political upheavals, pos-sibly resulting in the cancellation of the contracts by the new governments and leaders and hence the loss of the company’s investment. A very much higher level of legal stability is afforded by marine mining in international waters (“the Area”), which is properly regulated under ISA licences, with reliable contract periods and firm agreements.

Can oil disasters be prevented in future?

Marine mining is still a vision for the future. Offshore oil production, on the other hand, is a long-established industry which generates billions in profits every year. Unlike marine mining, however, the oil industry’s environmental and safety standards were not established before extraction commenced, but have been developed over time – generally in response to accidents or larger oil pollution incidents. In compliance with UNCLOS, most countries now have environmental legislation and regulations for offshore oil production, but accidents and spills still occur. There is a concern that the number of major oil spills will increase in future as a result of the trend towards drilling at ever greater depths, and that these incidents will be almost impossible to control, as was the case with Deepwater Horizon, for example.

Much thought has therefore been given to ways of improving the situation. Two key issues arise here: firstly, how incidents can be avoided and the environment can be protected, and secondly, who is liable in the event of a disaster. Experts propose the following solutions:- better safety standards and more stringent controls for the operation of drilling and production rigs;

- clearly defined liability in the event of an incident occurring;

- creation of funds to pay for clean-up operations after major spills and to provide compensation swiftly and with minimal red tape to injured parties.

- 4.10 > The operation of nuclear power plants, such as the one seen here at Onagawa, 80 kilometres north of Fukushima on the east coast of Japan, is classed by jurists as an “ultrahazardous activity” because accidents at industrial plants of this type can have extremely serious and far-reaching consequences.

- The issue of liability, in particular, is currently the subject of intense debate. When an incident occurs, public attention generally focuses on the facility operators, on the grounds that they have failed to comply with national safety and environmental standards. The ensuing legal disputes often drag on for years, greatly delaying the payment of compensation to injured parties. However, the states with jurisdiction over the area in which the installations are located also bear responsi-bility.

The situation becomes more complicated if neighbouring countries’ waters are polluted as well. One example is the fire at the Montara wellhead platform in the Timor Sea, off the northern coast of Western Australia, in 2009. This incident was very similar to the Deepwater Horizon disaster. The blowout released between 5000 and 10,000 tonnes of oil, contaminating Indonesian fishing grounds. The Montara platform was located in the Australian EEZ, but Australia refused to pay compensation. The question, then, is how state liability and payment of compensation can be regulated more effectively in future.

Guaranteed compensation after tanker incidents

The situation would be much simpler if a uniform set of rules on liability were adopted and recognised at international level, also governing the payment of compensation to injured parties. This type of international liability regime, which would be binding on all states, makes sense not only for the oil industry but for all other ultrahazardous activities in the EEZs or on the continental shelves as well. The term “ultrahazardous activity” is used by jurists to denote activities which, although not prohibited, can cause accidents that involve a substan-tial risk of harm, particularly transboundary pollution. Examples are the operation of nuclear power plants, chemical works and, in this case, oil drilling rigs. It is uncertain whether states will agree to adopt common rules.

Such an approach is entirely feasible, however. The International Convention on Civil Liability for Oil Pollution Damage was adopted for tanker operations back in 1969 and was updated in 1992. With this Convention, there is now a binding legal regime at international level for dealing with civil claims for compensation for oil pollution damage involving oil-carrying ships. Its main purpose is to ensure that compensation is paid swiftly and without excessive red tape to injured parties following tanker incidents. Legal proceedings are instituted before the courts of the state where the incident took place. The Convention, which has been ratified by 109 countries, establishes a robust international liability regime based on the application of uniform rules. Often, international civil law proceedings become very protracted because there are major differences between countries’ legal systems. For example, there may be different legal language, procedures and time limits, such as periods of limitation. What’s more, a legal dispute may drag on because conflicting evidence is submitted in expert opinions and second opinions, with the result that injured parties receive no compensation at all. Often, legal disputes centre on the question of fault: in other words, who is responsible for the damage. Another contentious issue, very often, is whether an incident could have been averted had parties acted differently. Thanks to the Convention, this is no longer relevant in relation to tanker incidents, for the Convention places liability for such damage on the owner of the ship from which the polluting oil escaped or was discharged. This liability, in general, is strict: in other words, it applies whether or not the owner is at fault or could have averted the damage. There are only a few specific exceptions, such as civil war or a natural disaster of an exceptional character, in which no liability for pollution damage attaches to the owner.

4.12 > The oil slick from the Hebei Spirit tanker, which was holed off South Korea in December 2007, polluted many kilometres of coastline. The authorities mobilized 12,000 clean-up workers, who attempted to remove the oil, sometimes using very basic equipment such as buckets and shovels. The costs of this type of clean-up operation are immense.

4.12 > The oil slick from the Hebei Spirit tanker, which was holed off South Korea in December 2007, polluted many kilometres of coastline. The authorities mobilized 12,000 clean-up workers, who attempted to remove the oil, sometimes using very basic equipment such as buckets and shovels. The costs of this type of clean-up operation are immense.Compensation payments from one large fund

Because the owner of the ship from which polluting oil escaped or was discharged bears strict liability, the Convention establishes a system of compulsory liability insurance for owners. Under the Convention, the costs of damage are initially met by the shipowner’s insurer. If the costs of damage exceed the amount provided under this insurance, a compensation fund comes into operation and, in a multi-stage process, meets further costs up to an amount of approximately 1 billion US dollars. This International Oil Pollution Compensation Fund (IOPC) was established under the International Convention on Civil Liability for Oil Pollution Damage. The Fund guarantees that injured parties actually receive compensation. It covers the costs of clean-up operations after tanker incidents and makes compensation payments to injured parties such as fishermen and the tourism industry. The oil-importing nations pay contributions into the Fund, which they then claim back from their national oil-processing industry. The rate of the contributions to be paid is based on the volume of oil imported.

The appealing aspect of the Fund is that payments are made immediately after an incident, irrespective of the question of fault – in other words, regardless of whether the incident was caused by human error on the part of the tanker captain or by the shipowner’s failure to properly maintain the vessel. This is critical, especially in situations when insurance payments are delayed as a result of legal disputes. The injured parties receive compensation from the Fund swiftly and without excessive red tape.

In some cases in the past, the Fund has negotiated directly with injured parties, thus avoiding lengthy delays in payment of compensation and removing the need for the parties concerned to pursue the matter through the courts. Once the Fund has compensated the victims, it can reclaim the money from the shipowner or his insurer. The Convention and the Fund form a two-pronged instrument that is both unique and unbeatable: the Convention creates legal certainty, and the Fund ensures that compensation is disbursed after every single incident in which damage occurs.

No fund for drilling rigs

The Convention and the IOPC Fund were developed in conjunction with the International Maritime Organization (IMO) and apply solely to vessels, not to fixed installations such as drilling rigs or anchored semi-submersible platforms. Although a similar model is conceivable in principle for these installations as well, there appears to be little interest on the part of the oil industry. At present, oil companies are covered by insurance, but this is merely general liability insurance up to an amount of 1.5 billion US dollars. Some drilling projects are uninsurable. But as the explosion at the Deepwater Horizon rig showed, this kind of general liability insurance does not come close to covering the costs of dam-age caused by a major oil spill. Nonetheless, the oil companies rejected an insurance scheme developed by reinsurers over a period of several years, which would have covered individual drilling projects and provided a 10 to 20 billion US dollar payout for environmental damage and follow-up costs. Experts believe that there is a very simple reason why the oil companies rejected the scheme: the oil companies are so wealthy that they regard this level of insurance cover as irrelevant. The interest in a liability convention and fund modelled on those in place for tanker incidents is correspondingly low. This is regrettable, for such a scheme would make legal disputes or proceedings after oil rig disasters a much less common occurrence in future.

Strict liability

Experts in the Law of the Sea regard a strict form of civil liability, such as that which now applies to tanker operations, as ideal. However, the adoption of conventions governing liability for other types of ultrahazardous activity, thereby establishing a uniform civil liability regime at the international level, is likely to be some years away. A transitional solution could be to introduce new regulations on state liability, meaning that it is the state, in every case, which covers damage caused by ultrahazardous activities, rather than a private company. At present, a state is only liable if it breaks the rules – for example, because its legislation or regula-tions are inadequate or because it has failed to fulfil its supervisory obligations in respect of chemical plants or drilling rigs. In order to avoid protracted legal disputes over issues of liability, a system that jurists term “strict state liability regardless of fault” may be a viable solution for ultrahazardous activities. This means that the state is always liable, regardless of whether or not the operator of the installation is at fault. Similar situations are familiar in every-day life. If a dog bites a child, the dog owner is liable in every case, whether or not he has trained his dog properly and sent it to dog training classes – in other words, whether or not he is at fault. He is “liable regardless of fault”. There are good arguments for introducing this form of liability for the operation of drilling rigs as well, for it is, after all, the state which authorizes the performance of this “ultrahazardous activity”. Furthermore, in many cases, states issue licences to companies, often charging very substantial licence fees, and thus have a stake in the company’s profits. If this form of state liability were introduced, protracted lawsuits and disputes, such as those which arose between Australia and Indonesia in the case of the Montara platform, could be avoided.

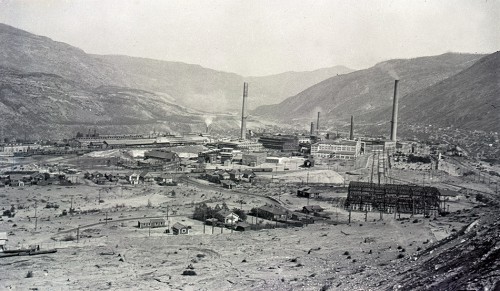

- At present, the concept of state liability is only enshrined in international law for large-scale transboundary pollution: here, international law establishes liability for culpable behaviour that violates the rules. The principle is enshrined at the highest level of international law and customary international law. It was first recognised in international jurisprudence more than 70 years ago as a result of the Trail Smelter case – the first major transboundary pollution incident – in the 1920s. Smoke from the Trail Smelter in Canada, which processed lead and zinc, had contaminated Canadian farmers’ fields in the surrounding area and caused damage to crops. The Canadian operator responded by building tall chimneys, so that the toxic smoke would be transported away from the fields. As a consequence, the pollution reached Canada’s neighbour, the USA, and destroyed US farmers’ crops. Compensation was paid out to the Canadian farmers very quickly, but lawyers acting for the US farmers and the Canadian company failed to reach an agreement on compensation. The case was therefore referred to the International Joint Commission (IJC), an independent binational organization established in 1909 to negotiate agreements on boundary waters between the USA and Canada. The arbitration process became extremely protracted because the parties disputed to what extent the damage to crops was in fact caused by smoke. A final decision was not reached until 1941. The company made a relatively small payout to the US farmers.

- 4.13 > The Trail Smelter in the Canadian province of British Columbia became famous for a legal dispute between Canada and the USA. It took years for US farmers to receive compensation for damage to crops and soil contamination.

Space law for earthly problems?

“Strict state liability regardless of fault” is not yet a real-ity. What’s more, because states enjoy immunity, a citizen or affected country cannot pursue, let alone enforce, legitimate claims through courts. In fact, international law and international customary law leave unanswered the question of how justice is to be done when damage occurs, and it is unclear which institution should dispense justice or fix penalties in such cases. The ques-tion, then, is whether, and how, a state can bring legal action against another state or force it to pay compensation. Due to the lack of clear rules, states generally reach agreement via diplomatic channels, often behind closed doors, which means that the injured parties cannot influence the process. After the Deepwater Horizon disaster, Mexico received compensation for the finan-cial losses caused by the oil pollution, but this was achieved as a result of diplomatic negotiations with US authorities. There is still only one instance of “strict state liability regardless of fault” being enforceable at the international level, namely in space law. Under the Convention on International Liability for Damage Caused by Space Objects, adopted in 1972, another state may, in respect of damage sustained in its territory due to the crashdown of a space object, present a claim to the launching state. As a general principle, the state from whose territory a space object is launched is liable.

For all other cases of transboundary pollution or damage, the situation continues to be problematical. Without a uniform international regime on civil liability for particularly high-risk activities in deep-sea mining or offshore oil production, there are currently only two options for obtaining justice or compensation: either to bring an action before the courts of a foreign state, or to reach an amicable agreement on compensation between the home state and the polluting state. In the majority of cases, however, both options are likely to involve a tough battle for justice.

Prevention – the best strategy

A clear liability regime and rules on compensation are important in order to make good any damage that occurs. Far more important, however, is to prevent environmental pollution in the first place. To that end, stringent technical safety standards occurs. Far more important, however, is to prevent environmental pollution in the first place. To that end, stringent technical safety standards are required. Here, the regulations applicable to oil-carrying ships serve as a good example. The re-quirement for tankers to be fitted with a double hull ensures that unlike the situation in the 1960s and 1970s, damaged tankers do not immediately start to spill oil. This has done much to avoid major incidents and pollution. Political benchmarks have also been set, with the adoption of agreements that declare certain areas of the sea completely off-limits to tanker traffic. There are several reasons why such high standards have been set in this particular industry. Firstly, tanker incidents have a significant media impact. The public pressure on policy-makers increased considerably from one oil disaster to the next. Furthermore, the principle of cause and effect is very straightforward in the case of an oil spill. If a captain runs his vessel aground, the circumstances which led to the grounding can generally be determined very quickly. On an oil rig, on the other hand, there are many people working simultaneously all over the installation, which means that clarifying the causes of an explosion is more difficult. There are many activities that are critical to security in the operation of a rig, and these can be analysed and improved. This in turn is an argument in favour of a liability regime similar to that which exists for tanker incidents. A liability convention would create an obligation for rig operators and oil producers to contribute to a fund. As with the IOPC Fund, injured parties would then receive compensation swiftly, before the complex question of fault and the cause of the incident have been clarified. The adoption of a relevant convention and creation of a fund would also be a major step towards a new culture of safety in offshore operations, which is now wellestablished in the tanker industry.

Reducing consumption

Unfortunately, some environmental damage from industrial operations will always occur. The key task, therefore, is to reduce this damage to an absolute minimum. As long as people need resources, the extractive industries will have an adverse effect on habitats. The most important question, then, is how consumption of these resources can be reduced. One way forward is to develop recycling technologies and set up supply chains for reusable materials. Even in the established recycling industries, there is still room for improvement: one example is aluminium, with only around one third currently being recovered. All over the world, companies are working intensively to develop new processes for the recovery of special metals, such as rare earth elements, from computers and smartphones. These devices offer great potential for recycling as they are available in very large quantities, contain large amounts of special metals, and have short lifecycles. This means that the metals can be recovered and made available to the primary industry very quickly.

- Furthermore, many environmentally sound and energy-efficient technologies now exist. Solar and wind energy plants and energy-efficient vehicle drive systems have reached a sophisticated stage of development. Dispensing with consumption is also helpful, for resources that are not consumed do not need to be extracted in the first place. The Western industrial nations in particular have maintained a very high level of consumption for some time. The transformation of the industrial nations into consumer societies began after the Second World War. Philosophers and social scientists refer to “1950s syndrome” – the period of rapidly rising living standards from 1949 to 1966, when energy consumption increased dramatically. At that time, supplies of energy and raw materials appeared to be inexhaustible and were correspondingly cheap.

This was reinforced by the discovery of major oil fields in the Middle East and the development of nuclear energy. There was enough oil, it seemed, to last for centuries. Food also became more affordable as a result of intensive farming and animal husbandry, which in turn were made possible by intensive use of machinery and energy. This era, researchers claim, was a historical anomaly and far from being the norm. We recognise this today, for we are now faced with increasing resource scarcity and a rapidly growing world population.